ABBREVIATIONS

BPW, buffered peptone water; LED, light-emitting diode; NB, nanobubble; NC, nanocrystal; PCA, plate count agar

INTRODUCTION

The highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) is one of the fruit whose consumption has been increasing in the last years due the important health properties of the species. The fruit quality is affected by the interaction of abiotic and biotic factors that can occur along all the supply chain (from the orchard to the post-harvest phase). Berries can be consumed fresh or stored frozen mainly and, as a consequence, these two major steps in the supply chains generate different quality requirements. The visual appearance (skin bruising and softening) and the shelf-life are the main attributes for the fresh market while the maintenance of nutritional and health value is required after the processing phase in the food industry. Diseases caused by fungi, bacteria and viral spoilage organism are the greatest cause of post-harvest losses in berries. The high humidity conditions in the storage phase, that are necessary to maintain the freshness of fruits, represent a critical factor in the berries supply chain if there is no adequate air flow to prevent moisture condensation on berries skin [Almenar et al., 2007]. The main post harvest phytopathological disorders caused by fungi and some bacteria can in fact compromise the marketability of the berries up to 20% if they are not properly managed along all the supply chain [Bell et al., 2021]. The gray mold caused by Botrytis cinerea, Rhizopus rot by Rhizopus stolonifera and anthracnose fruit rot (black spot) by Colletotrichum acutatum and Colletotrichum gloesosporiodes are the most common diseases. Phytophthora cactorum, Cladosporium sp., Fusarium sp. and Alternaria sp. occasionally occur on berries [Bell et al., 2021; Ding et al., 2023]. The incidence of Botrytis on fresh fruits (after prolonged cold storage) is not influenced by conidial density on the surfaces, but by the resistance level of the host [Jiang et al., 2022]. In the case of Rhizopus instead the development is on overripe berries, but the fungi cannot grow below 5°C [Bell et al., 2021].

The main actors involved in the production, transport, handling, display, and sale of berries are responsible for the fruit safety. This is a very important and complex issue for the fresh supply chain. To extend blueberries shelf-life different approaches have been explored in the last years. The most common used were the cold atmospheric pressure plasma [Bovi et al., 2019; López et al., 2019], the use of coating with bio-films [Maringgal et al., 2020; Nain et al., 2021; Sempere-Ferre et al., 2022], the pulsed light [Pratap-Singh et al., 2023] and the UV-B application [Varaldo et al., 2024]. Nanotechnology applications could potentially address many of these needs due their large versatility bringing revolution in the agri-food supply chain from production, processing, packaging and transportation to storage. Different nanodelivery systems, such as nanoliposomes, colloidosomes, nanoemulsions, nanofibers, and polymeric nanoparticles, together with their application have been studied by food technologists exploiting proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids among ingredients to provide benefits in the food sensory attributes or to enhance the efficacy of the nanodelivered bioactive compounds [Biswas et al., 2022]. Considering that research on the application of nanovectors in fresh fruits, in particular blueberries, are still limited [Jafarzadeh et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2024; Stura et al., 2023], it seems interesting to evaluate this tool to improve the shelf-life of berries as innovative post-harvest management. The present work describes a preliminary approach to evaluate the antimicrobial effect in vitro of two curcumin-based nanostructures, such as curcumin-loaded nanobubbles (NBs) and curcumin nanocrystals (NCs), alone and under photoactivation with a white- and blue light-emitting diode (LED). The encapsulation of curcumin in NB system has been previously optimized [Bessone et al., 2019; Munir et al., 2023]. This preparatory approach proposed might be the first step towards the study, development, and application of a storage treatment for freshly picked berries with natural compounds (curcumin) with the support of the nanotechnology tool. The development of a new type of photoactivated coating for berries during post-harvest aims to preserve and extend shelf-life and exploit natural compounds without costly and high-impact treatments, such as freezing and high-pressure techniques. This method could address the solutions for sustainability and resource optimization strategy in the agri-food supply chain. Fruit safety is an intrinsic requirement in the supply chain as also the control of phytopatological disorders. Hence, this study aimed at tentative evaluation of the in vitro antimicrobial activity of different nanocarriers in the blueberry post-harvest phase, investigating the optimum concentrations, nanostructure and the role of the photoactivation of curcumin from Curcuma longa L.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fruit material and bacterial extraction

Blueberries imported from Peru were retrieved from a supermarket in Grugliasco (Italy) and directly taken to the Department of Agricultural, Forest and Food Sciences (DISAFA), University of Turin, Grugliasco (Italy) to isolate microorganisms.

Notably, 20 g of blueberries were weighed and placed in a stomacher bag with 180 mL of buffered peptone water (BPW, Scharlab srl, Lodi, Italy). A suspension was prepared by smashing the berries in the stomacher (Seward, Worthing, United Kingdom) for 30 s at 2,300 rpm. Subsequently, 100 μL of the suspension was inoculated into Petri dishes with a plate count agar (PCA, Scharlab srl) and incubated at 30°C for 48 h. The grown colonies were randomly selected and picked, then resuspended in about 40 mL of a Ringer’s solution, reaching a concentration of 7 log CFU/mL using a McFarland standard turbidity scale (Biomerieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France). The microorganisms were directly isolated from commercially available blueberries and not purified.To prepare the suspension, colonies were screened for morphology, and a representative number of morpho-type was selected on PCA plates. This selection was performed to obtain a representative broth culture of the blueberry bacterial microbiota. The suspension was homogenized using a vortex to eliminate cell aggregates. The final broth (750 µL) was dispensed in 2 mL tubes with glycerol (250 µL) to allow a long-term storage at −18°C without affecting the vitality of the cells. The bacteria were revived for 48 h before the experiment (1 mL of bacterial suspension inoculated in 30 mL of brain-heart infusion broth (BHI) and incubated at 30°C), to obtain an initial suspension of microorganisms. A dilution-streak plate was made from the broth culture used to screen the various morphologies growing in it.

Preparation of curcumin nanoformulations

Curcumin from Curcuma longa L. (Sigma-Aldrich, Merk Life Science S.r.l., Milan, Italy) was used to prepare two nanoformulations, i.e., curcumin-loaded NBs and curcumin NCs. For the preparation of curcumin-loaded NBs, curcumin was dissolved in Epikuron 200 (Cargill, Minneapolis, MN, USA) (3%, w/v) and palmitic acid (0.5%, w/v) ethanol solution by using N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone as a co-solvent. The mixture was then added to decafluoropentane and distilled water and homogenized using an Ultra-Turrax homogenizer (IKA, Staufen im Breisgau, Germany) for 2 min. Subsequently, an aqueous solution of chitosan (2.7%, w/w, pH 4.5) was added under magnetic stirring [Munir et al., 2023]. Three different formulations were prepared with curcumin concentrations of 25, 50 and 100 µg/mL, respectively.

Curcumin NCs were prepared by wet media milling method using a planetary ball mill (PM 100, Retsch, Haan, Germany). An aqueous suspension of curcumin (5%, w/v) was prepared and added into the milling chamber containing milling pearls (3 mm stainless-steel grinding balls). The milling process was performed at 400 rpm for 2 h, with a pause of 5 min at every 30 min rotation [Malamatari et al., 2018]. Different dilutions (0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mg/mL) of the produced curcumin NC nanosuspension were prepared in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for the microbiological assays. At least ten different formulation batches for curcumin NBs and NCs were produced.

In vitro characterization of curcumin nanoformulations

The average diameter, polydispersity index and zeta potential of the curcumin formulations (i.e., NBs and NCs) were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a 90 plus instrument (Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, New York, NY, USA), at a fixed scattering angle of 90° and a temperature of 25°C. The samples were diluted in filtered distilled water prior to measurements.

The dissolution profile of curcumin NCs was evaluated in water by suspended weighed amounts (5 mg) of curcumin NCs in 50 mL of distilled water under magnetic stirring at room temperature. At fixed times (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 h), 500 µL samples were withdrawn and replaced with the same amount of fresh dissolution medium. After centrifugation and filtration through a membrane filter (0.22 µm), the content of curcumin in the samples was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis [Argenziano et al., 2022]. A Shimadzu system (Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a UV/Vis detector set at a wavelength of 425 nm was used to this end. The analysis was performed using a mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile and water (70:30, v/v) at 1 mL/min flow rate through a reverse phase TC-C18(2) column (250 × 4.6 mm, pore size 5 µm, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The in vitro release kinetics of curcumin from curcumin-loaded NBs was determined using a multi-compartment rotating cell system. The curcumin-loaded NBs were placed in the donor chamber separated from the receiving compartment through a dialysis cellulose membrane (Spetra/Por cellulose membrane, cut-off 14 kDa, Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA, USA). The receiving phase contained PBS supplemented with 0.1% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). At fixed times (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 22, 24, 28 h), the receiving phase was withdrawn and replaced with the same amount of fresh PBS [Bessone et al., 2019]. The withdrawn samples were analyzed by HPLC to determine the curcumin content as described above. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

In vitro antibacterial activity determination by well diffusion method

The antimicrobial effect was tested using agar diffusion method as presented by Nadjib et al. [2014] with minor modifications. In particular, in all the trials the initial microbial concentration was 6 log CFU/mL, where 1 mL of the initial microbial suspension was added to 9 mL of fluid PCA and poured into a Petri dish. After the media solidified, 1.5 mm wells were made using the edge of a sterile glass pipette. Curcumin suspensions were inoculated without dilutions, using 20 μL into each well. Wells cut in agar were chosen instead of disks for practical reasons – very small quantity of nanocarriers suspensions. A suspension (20 µL) of three NBs (with curcumin concentrations of 25, 50 and 100 µg/mL) or three NCs (with curcumin concentrations of 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mg/mL) (separate plates for treatments with NBs and NCs) and a sterilized Ringer’s solution (as the negative control) were inoculated into each well. Six plates were prepared for each lighting condition (white LED, blue LED, dark). After preparation and photoactivation, plates were incubated at 30°C to allow microbial growth, and inhibition halos (mm) were determined as follows:

where: ϕ is the diameter.Photoactivation and storage conditions

The NBs-inoculated plates (first trial) and NCs-inoculated plates (second trial) were photoactivated with white and blue LEDs at refrigerated temperature (4°C) for 3 h. Thanks to the freezing procedure with glycerol it has been possible to use the same bacterial mixture for both trials. Petri dishes were arranged under the LEDs to be homogeneously lit on the plate surface independently from their relative position. Incubation at 30°C for 48 h followed to allow the bacterial growth. Besides white LED and blue LED, six plates per trial were also kept in the dark, as a reference. Six replicates for each curcumin-loaded nanovector, under each LED color (white and blue) were considered.

Statistical analysis

The in vitro antimicrobial activity evaluation was performed with six replicates of each concentration of curcumin nanoformulation under each lighting condition. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out on the results of halos, separately for NBs and NCs, considering light color and curcumin concentration as factors. Statistically significant differences were identified by comparison of mean values through Bonferroni’s post-hoc test (p≤0.05). The R software 4.4.2 version (Free Software Foundation, Boston, MA, USA) was used for these elaborations.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

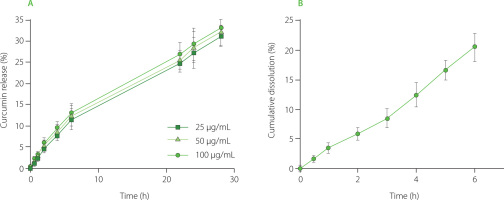

Two different curcumin nanoformulations were developed to evaluate the antimicrobial effect. In particular, curcumin NCs, a carrier-free curcumin colloidal nanosystem, were compared to a nanostructure in which curcumin was molecularly dispersed, such as curcumin-loaded NBs. Both formulations were characterized in vitro, evaluating the physicochemical parameters. Their average diameter, polydispersity index and zeta potential are shown in Table 1. NBs and NCs showed sizes in the nanometer range and good polydispersity indices. Indeed, the polydispersity index values of NB and NC formulations of about 0.2indicated a rather homogenous nanoparticle size distribution [Danaei et al., 2018]. No significant difference in NB average diameter was observed between the three NB formulations having different curcumin contents. All the NB formulations exhibited a positive surface charge with zeta potential values of about +28 mV, due to the presence of the chitosan shell, while curcumin NCs showed a negative surface charge. Additionally, the curcumin release from NBs as a function of time and dissolution profile of NCs are presented in Figure 1. In particular, NCs (Figure 1B) dissolved more percentage of curcumin in less time in respect of NBs (Figure 1A), as expected. Indeed, NCs were pure curcumin agglomerates, while NBs had less curcumin, but their structure was able to release it slowly. A prolonged in vitro release profile of curcumin from NBs with no initial burst effect was observed, indicating the curcumin incorporation in the NB core (Figure 1A). NCs, instead, enhanced the dissolution rate of curcumin due to the increased surface area and saturation solubility.

Table 1

Physicochemical characteristics of curcumin nanocrystals (NCs) and curcumin-loaded nanobubbles (NBs).

Figure 1

(A) In vitro release profile of curcumin from curcumin-loaded nanobubbles (NBs) formulations at different curcumin concentrations and (B) in vitro dissolution profile of curcumin nanocrystals (NCs).

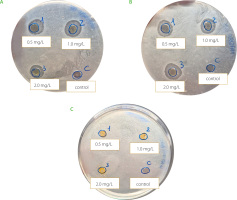

Curcumin-loaded NBs and curcumin NCs have been evaluated in vitro, under photoactivation with white or blue LED, on the microbiota extracted from blueberries and all showed an antimicrobial effect (Figure 2 and 3). The antibacterial effect was not perceivable in terms of halo presence for the samples incubated under no light (Figure 2C and 3C), concluding that the presence of light is fundamental to boost the activation. Considering NBs, the results from halos analysis highlighted a significant difference between both white and blue LEDs and for the different curcumin concentrations (Table 2). The antibacterial effect of the application of white light was less impactful as the mean halo dimension was smaller compared to blue light (p≤0.05). Concentration effect was not statistically significant between 50 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL and between 25 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL (p>0.05). These results encourage the fact that a smaller dose with respect to 100 μg/mL may have a more significant and valuable antimicrobial efficacy. Regarding NCs, no significant difference (p>0.05) was evident, for white or blue LEDs (Table 2). The lack of differences observed for NC formulations may be attributed to the nanovector structure. NBs are nanometric core-shell structures, in which curcumin is molecularly dissolved in their inner core, made of decafluoropentane, a perfluorocarbon. The NB structure can affect the antimicrobial efficacy of curcumin favoring the delivery of curcumin molecules and their interaction with the fruit matrix. Therefore, this capability has an impact on the availability of the active ingredient (curcumin). Moreover, it has been reported that the encapsulation can have a role in retarding the curcumin degradation [Naksuriya et al., 2016]. Indeed, the rapid degradation of curcumin as such limited its possible application. In addition, a synergic antimicrobial effect can be obtained thanks to NB chitosan coating, although this property was not investigated in this experimental work. It is worth noting that the chitosan had antimicrobial activity [Confederat et al., 2021]. The results obtained should be considered as preliminary and evaluated as screening. Generally, they disclosed the potential of NBs and NCs coupled to light to inhibit bacterial communities, but this cannot necessarily be translated into a clear proof of inhibition against spoiling bacteria and improvement of fruit quality. Further assays should investigate the effect on specific pure bacterial cultures considered fruit spoiling agents but also on the main fungal diseases affecting berries, to have a complete assessment of the treatment efficacy.

Figure 2

Inhibition halos caused by nanobubbles (NBs) loaded with curcumin at concentrations of 25, 50 and 100 μg/L. Sterile Ringer’s solution was used as a negative control. The plates were photoactivated with white LED light (A), blue LED light (B) and kept in the dark (C) at 4°C.

Figure 3

Inhibition halos caused by nanocrystals (NCs) loaded with curcumin at concentrations of 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mg/mL. Sterile Ringer’s solution was used as control. The plates were photoactivated with white LED light (A), blue LED light (B) and kept in the dark (C) at 4°C.

Table 2

Halo measurement results for curcumin-loaded nanobubbles (NBs) and curcumin nanocrystals (NCs) at different curcumin concentrations and different photoactivation modes.

[i] Data are reported as mean ±standard deviation (n=6). Different letters highlight statistically significant differences among the samples’ mean (p≤0.05). Light color and curcumin concentration were considered as factors of the two-way ANOVA. Nanobubbles (NBs) and nanocrystals (NCs) were investigated separately.

On the other hand, curcumin NCs are carrier-free pure drug crystals with a size in the nanometer range. Therefore, curcumin is not present at a molecular level but a dissolution step is necessary for its delivery on the fruit matrix. Moreover, no external adjuvant structure and no other ingredients were used to activate or amplify the curcumin effect, possibly justifying the absence of the doserelated effects. Notably, the NC structure was investigated to possibly extend the nanovector technology to food products, as the presence of a perfluorocarbon is not allowed in food due to safety reasons and is in no way included in the list of food additives authorized by the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union [Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008]. The promising results obtained with NBs pave the way for developing nanovesicles without perfluorocarbon for the delivery of curcumin.

This experiment aimed to define a microbiological in vitro protocol to screen the efficacy of the NBs and NCs nanosuspensions on the real microbiota present on the fruit reference, in this case blueberries. In fact, the preliminary phase should clarify if the further in vivo tests may have scientific significance, as different conditions and the non-homogeneity of the fruit matrix usually lead to uneven results, reduced or altered antimicrobial activity [Lichtemberg et al., 2016]. It is necessary to recognize a limitation of the methodology applied: the microbiological process followed was not previously compared to traditional and acknowledged one, performed on single pathogens or specific mix of relevantspecies. Thus, the conclusions cannot be generalized but are dependent on the microbiota present on the specific blueberries from which they were extracted.

The refrigeration temperature and the LED activation in the study should simulate the storage conditions of berries at the point of sale of the large-scale organized market, where the packaged berry fruits are kept at least overnight. Moreover, the cold chain may prevent possible damages of the fruit product caused by the heat deriving from light exposure. The possible effect of light on the fruit should be also considered. Both release patterns and LEDs efficacy are reported to work better at room temperature or even higher (50°C); however, these conditions cannot be applied in the fruit supply chain, as the product would be damaged [Liu et al., 2015]. The blue light was demonstrated to exert an antimicrobial effect on pathogenic bacteria, such as Escherichia coli [Braatsch & Klug, 2004]. Blue light spectrum should better match with curcumin activation. Nevertheless, also white LEDs were considered as their spectrum, because as reported by Vera-Duarte et al. [2021] they overlap to a large extent with the blue light spectrum. Moreover, white LEDs are currently used in the illumination system of refrigerated counters at large retailers.

When assuming the use of nanocarriers and nanosolids in a food context, a complete assessment of their impact on the safety and sensory quality of the product is required. As previously discussed, the presence of perfluorocarbon in NBs is the first issue. After considering this primary aspect, the sensory aspects should not be neglected. The addition of an ingredient and possible structures containing it may cause changes in the traditionally perceived flavor. Many research studies in literature focused on the possibility of introducing nanoparticles in the pharmaceutical sector to reduce the taste and aftertaste of medicines and drugs, especially for pediatric patients [Krieser et al., 2020; Naik et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022]. In agreement with these studies, the presence of a nanovector covering the active ingredient should encapsulate the curcumin flavor, certainly in relation to the structure and composition of the nanostructure itself and proportionally to the applied dose. The evaluation of the possibility of color release onto the berries surface needs to be investigated as appearance is the first and primary interaction point between the fruit product and the consumer during the purchase.

In relation to the analytical methodology adopted, it is meaningful to remark that the overall microbiota present on the blueberry surface may be constituted of strains acting as biocontrol agents with antagonistic effect on the main fungal pathogens [Chacón et al., 2022], thus further characterization of the bacteria extracted may help in defining the range of activity of the curcumin-loaded nanostructures.

CONCLUSIONS

Producing and managing fresh berries in a sustainable way meeting market and consumers’ high-quality requirements is the key for the future challenge in the post-harvest sector. This study provides a first insight into understanding how curcumin NBs and NCs under photoactivation act against a bacterial mixture isolated from blueberries. Results validate the positive role of these innovative tested treatments in the in vitro inhibition of bacteria isolated from the fruit matrix. This may help evaluate the treatment for the further application of the methodology in vivo. The approach followed in this study is a mandatory step to understand the feasibility of a post-harvest protocol for blueberries’ management treated in vivo with nanocarriers. Further studies are needed to consider the feasibility and applicability of the technique and especially the knowledge of the raw material in terms of the picking time and conditions before the management in the laboratory should be considered.In fact, all storage treatments normally used in the picking store (use of modified atmosphere or controlled atmosphere) could directly affect the results of the study. Thus, the interaction between nanocarrier treatment and other post-harvest storage technique should be considered for further investigations.