INTRODUCTION

In recent years, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, consumer preferences have undergone significant changes. While carbonated soft drinks were once the dominant choice, there is now an increasing shift toward refreshing and health-conscious beverages. Water kefir has gained popularity as a functional drink valued for its enjoyable taste – mildly sweet, tangy, and effervescent, and its potential numerous health benefits. These include probiotic qualities, the ability to inhibit harmful bacteria, antioxidant activity, healing support, immune system modulation, digestive assistance, ulcer prevention, liver protection, reduction of blood lipid levels, and regulation of blood sugar [Bozkir et al., 2024; Moretti et al., 2022]. This rising awareness of health advantages has driven the rapid growth of the global water kefir market, which was valued at $1.23 billion in 2019 and is expected to reach $1.84 billion by 2027 [Moretti et al., 2022].

Water kefir grains contain a complex community of microorganisms, including lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, and Streptococcus), acetic acid bacteria (primarily Acetobacter), and yeasts (Saccharomyces, Zygosaccharomyces, and Brettanomyces) [Moretti et al., 2022]. The health-promoting effects of water kefir are largely attributed to microorganisms residing within the grains. For instance, Lentilactobacillus hilgardii, Lacticaseibacillus paracasei, Liquorilactobacillus satsumensis, Lactobacillus helveticus, Lentilactobacillus kefiri, Saccharomyces paradoxus, and Saccharomycodes ludwigii isolated from water kefir grains exhibit probiotic characteristics [Romero-Luna et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2022b]. These microorganisms have demonstrated antimicrobial activity against intestinal pathogens, strong antioxidant capacity, and viability in simulated gastrointestinal conditions [Romero-Luna et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2022b]. Notably, Lactobacillus mali APS1 has shown potential in reducing liver fat accumulation in rats fed a high-fat diet by modulating lipid metabolism and enhancing antioxidant defenses [Chen et al., 2018]. Beyond the beneficial microorganisms, bioactive metabolites generated during fermentation also significantly contribute to the health benefits of water kefir. Lactic, acetic, propionic, and malic acids are renowned for the antimicrobial effects of water kefir [Bozkir et al., 2024]. Soluble exopolysaccharides, including O3- and O2-branched dextrans and levans, are believed to enhance antimicrobial, antioxidant, and prebiotic properties while phenolic compounds are significant contributors to the antioxidant capacity of the beverage [Azi et al., 2020; Fels et al., 2018].

Traditionally, water kefir is prepared by inoculating grains into sugary water, often supplemented with dried figs and lemon slices [Moretti et al., 2022]. However, a variety of other substrates, such as plant juices or even protein sources, can also be used for fermentation [Alrosan et al., 2023; Corona et al., 2016; Ozcelik et al., 2021]. Using alternative substrates may lead to increased production of bioactive compounds, thereby improving the health benefits of water kefir. A prior research found that water kefir made from coffee cherry showed superior levels of organic acids, phenolics, and amino acids compared to unfermented sample, resulting in higher antioxidant capacity and antibacterial effects on foodborne pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus subtilis [Chomphoosee et al., 2025]. Similarly, fermenting soy whey with water kefir elevated levels of isoflavone aglycones and phenolic acids, boosting its free radical-scavenging and ferric reducing antioxidant power abilities [Azi et al., 2020]. These studies underscore the potential for exploring diverse substrates to create innovative water kefir products.

Edible bird’s nest (EBN) is a highly prized delicacy in China, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines. It is produced from the nests built by swiftlets belonging to the Aerodramus and Collocalia genera, which are plentiful in Southeast Asian countries [Dai et al., 2021]. Known as one of the most expensive animal-derived products, EBN can cost between $1,000 to $10,000 per kilogram, due to its reputed nutritional and medicinal benefits. The primary composition of EBN is proteins, predominantly glycoproteins, accounting for 62–63% of EBN dry weight [Kathan & Weeks, 1969; Marcone, 2005]. Besides proteins, it contains other components such as carbohydrates (25.62–27.26%), minerals (2.1%), and lipids (0.14%–1.28%) [Marcone, 2005]. The glycoproteins include 9% of sialic acid, 7.2% of galactosamine, 5.3% of glucosamine, 16.9% of galactose, and 0.7% of fructose [Kathan & Weeks, 1969]. Traditionally, EBN has been used in folk medicine to help clear phlegm, reduce coughing, combat fatigue, and aid recovery after surgery. Modern scientific studies have highlighted its antioxidant, antiviral, antibacterial, anti-tyrosinase, anti-aging, and immune-boosting properties [Dai et al., 2021].

EBN is conventionally prepared for soup through double boiling; however, this method results in low solubility, limiting its nutritional and therapeutic potential. Alternative techniques such as over-boiling and enzymatic hydrolysis have been explored to address these issues [Wong et al., 2017]. As fermentation with water kefir has been applied to improve the biological properties of foods [Tu et al., 2019], the current study attempts to investigate EBN water kefir, focusing on its antioxidant, anti-tyrosinase, and probiotic growth-promoting properties. Additionally, total phenolic content and protein profile are analyzed to understand how changes in phenolics and proteins influence the biological effects of the fermented product. Our findings aim to develop an effective method for producing a health-promoting beverage and making EBN-based products more affordable and accessible worldwide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of edible bird’s nest water kefir

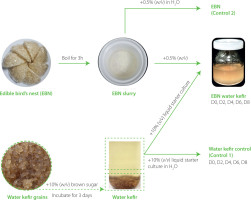

White, house-farmed EBN cups were kindly supplied by Phuoc Tin Development Trading Service Co., Ltd. (Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam). The EBN slurry was prepared by boiling 0.5 g of EBN in 100 mL of distilled water (0.5%, w/v) for 3 h to enhance the solubility of the EBN glycoproteins and thereby facilitate fermentation. To create the starter culture, 15 g of water kefir grains, locally sourced from Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, were added to 300 mL of a 10% brown sugar solution and allowed to ferment at 25°C for 3 days as previously described [Alrosan et al., 2023]. After fermentation, 10 mL of the liquid starter culture were mixed with 90 mL of water or 90 mL of EBN slurry (10%, v/v) in a glass jar covered with sterilized cheesecloth. Fermented samples were collected every 2 days over an 8-day period, boiled at 100°C for 30 min, then centrifuged at 13,751×g for 15 min to separate the supernatants. The boiling and centrifugation steps were performed for all experiments, except for the direct counting of viable microorganisms. The pH of the supernatants was adjusted to 7.0. The EBN water kefir samples collected at day 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 of fermentation are herein referred to as D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8, respectively. The water kefir controls harvested at day 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 of fermentation showed similar results across all assays. Therefore, we presented representative data designated as control 1 in the figures for clarity and simplicity. Control 2, boiled EBN without starter culture, was stored at 4°C until all the EBN water kefirs and control 1 were prepared. The preparation of EBN water kefir and controls is summarized in Figure 1.

Determination of pH and total soluble solid content

The pH values of the control 1 and EBN water kefir samples (D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8) were assessed using a pH meter (Mettler-Toledo International, Inc., Greifensee, Switzerland). The total soluble solid content (ºBrix) in the samples were measured with a refractometer (Hana Instruments, Cluj Napoca, Romania).

Determination of microbial growth

The control 1 and EBN water kefir samples (D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8) were diluted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Sigma-Aldrich Pte. Ltd., Singapore). The populations of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), acetic acid bacteria (AAB), and yeasts were enumerated by plating the diluted samples on specific agar media: de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) agar (Oxoid Ltd., Cheshire, UK) supplemented with 400 mg/L of cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich Pte. Ltd.) for LAB; glucose-yeast extract-calcium carbonate (GYC) agar (composed of 40 g/L of glucose, 10 g/L of yeast extract, 30 g/L of CaCO3, and 15 g/L of agar) supplemented with 400 mg/L of cycloheximide for AAB; and potato dextrose (PD) agar (Oxoid Ltd.) for yeasts [Guangsen et al., 2021]. The plates were incubated at 35°C for 2 days for bacterial cultures and at 25°C for 2 days for yeast cultures. Microbial populations were expressed as colony-forming units (CFU) per mL of the samples.

Determination of antioxidant activity

The 2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) radical cation (ABTS•+)-scavenging capacity was determined following the previously established protocol [Nguyen et al., 2024b]. In brief, EBN water kefirs and control 2 were diluted to different concentrations (0.0078, 0.0156, 0.0312, 0.0625, 0.125, 0.25, and 0.5 mg/mL of the original EBN amount). For the assay, 900 μL of the ABTS•+ solution were mixed with 100 μL of each diluted sample and incubated at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. The absorbance was then measured at 734 nm using a microplate reader (VICTOR Nivo 3F, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). The capacity of the samples to scavenge ABTS•+ radicals was determined using Equation (1):

where: A1 is absorbance of the ABTS•+ solution with Milli-Q water instead of a sample, A2 is absorbance of the sample after reacting with ABTS•+, and A3 is absorbance of the sample without ABTS•+ (blank).

For the hydroxyl radical (•OH)-scavenging assay, 100 μL of diluted EBN water kefirs and control 2 (at concentrations of 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 mg/mL of the original EBN amount) were incubated with 20 μL of 9 mM salicylic acid for 20 min in a 96-well plate [Nguyen et al., 2025b]. Afterward, each well received 50 μL of a mixture containing 9 mM ferrous sulfate (FeSO4) and 100 μL of 8 mM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). The absorbance was then recorded at 530 nm using a microplate reader (VICTOR Nivo 3F, PerkinElmer). The •OH-scavenging capacity was determined using Equation (2):

where: A1 is absorbance of negative control (Milli-Q water), A2 is absorbance of the sample after reacting with salicylic acid, and A3 is absorbance of the sample without salicylic acid.

Determination of anti-tyrosinase activity

The tyrosinase inhibitory assay was conducted following a previously published method [Nguyen et al., 2024a]. In brief, 30 μL of mushroom tyrosinase enzyme (250 U/mL in PBS buffer, pH 6.8) (Sigma-Aldrich Pte. Ltd.) were combined with 100 μL of EBN water kefirs and control 2 at a concentration of 1.25 mg/mL of initial EBN in a 96-well plate. This mixture was then incubated in the dark at 28°C for 10 min. Subsequently, 110 μL of l-tyrosine substrate (0.3 mg/mL in PBS buffer, pH 6.8) (Sigma-Aldrich Pte. Ltd.) were added to each well. After another 10-min incubation at 28°C, the inhibitory activity of tyrosinase was measured by recording absorbance at 480 nm using a microplate reader (VICTOR Nivo 3F, PerkinElmer), to monitor dopachrome formation. The tyrosinase inhibitory capacity (TIC) of the samples was calculated as follows (Equation 3):

where: A1 is absorbance of negative control (Milli-Q water instead of a sample), A2 is absorbance of sample after reacting with tyrosinase, A3 is absorbance of the blank for the negative control without l-tyrosine substrate, and A4 is absorbance of the blank for the sample without l-tyrosine substrate.

Assessment of the growth of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactococcus lactis

The promoting potential of the EBN water kefir samples on the growth of the probiotic L. acidophilus ATCC 4356 and two potential probiotic strains isolated from Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa subsp. Pekinensis), L. lactis VLC.1 and L. lactis VLC.2, was assessed as previously described with some modifications [Nguyen et al., 2025b; Vu-Quang et al., 2024]. Following inoculation into a broth containing 2/3 de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) and 1/3 tryptic soy (TS) (Oxoid Ltd.) and incubation at 37°C for 24 h, the bacterial suspension was diluted to approximately 106 CFU/mL. A 100 μL aliquot of this suspension was then treated with a mixture containing 40 μL of each sample at a concentration of 1 mg/mL of initial EBN, combined with 60 μL of the 2/3 MRS and 1/3 TS medium. Optical density at 600 nm (OD600) measurements were taken every 2 h over a 24-h incubation period at 37°C to generate bacterial growth curves. After 24 h, probiotic growth was quantified by performing decimal serial dilutions in PBS buffer, followed by plating on 2/3 MRS and 1/3 TS agar plates, and counting the resulting colony-forming units (CFU/mL).

Determination of total phenolic content

The total phenolic content (TPC) in the samples was determined via the colorimetric assay with the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent [Singleton et al., 1999]. To begin, 400 μL of each sample of EBN water kefirs and control 2 was mixed with 400 μL of 10% Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (Sigma-Aldrich Pte. Ltd.). Subsequently, 400 μL of 10% sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) was added to the mixture, which was then incubated at 40°C for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a UV spectrophotometer (Genway Biotech, San Diego, CA, USA). Gallic acid (Sigma-Aldrich Pte. Ltd.) was used as the standard to plot a calibration curve. The equation of the calibration curve was y=0.021x+0.030 (R2=0.9995). The TPC results were expressed as μg of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per mL.

Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed following a previous protocol [Gallagher, 2006]. A volume of 1 mL of each sample (D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8) was freeze-dried to obtain a powder. These powders were then mixed with 20 μL of SDS-PAGE loading buffer, heated at 90°C for 30 min to denature the proteins, and subsequently loaded onto a 12.5% separating gel. Electrophoresis was conducted using a Bio-Rad Laboratories system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). After separation, the gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue for 2 h and then destained with a solution containing 10% absolute ethanol and 10% acetic acid to visualize the protein bands. A color prestained protein standard (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA) was used for molecular weight determination.

Sensory evaluation

The training procedure for panelists and the sensory evaluation test were conducted as previously described [Nguyen et al., 2025a]. Samples of original EBN water kefir (D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8) and water kefir (control 1) sweetened with 10% (v/v) rose syrup (Monin, Bourges, France) were assessed for sensory qualities, including appearance, color, odor, sourness, taste, and overall acceptability, by a panel of 10 trained evaluators (comprising 5 women and 5 men aged 20 to 40 years) at NTT Hi-Tech Institute, Nguyen Tat Thanh University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. A 9-point hedonic scale, where 1 indicates “dislike extremely” and 9 indicates “like extremely” was used to measure each sensory attribute. The results provided an initial evaluation of the sensory attributes of EBN water kefirs. Additional studies involving a larger number of participants are needed to obtain more definitive insights into consumer preferences and the overall acceptability of the product.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed on samples from three independent fermentations. Statistical comparisons in the assays were conducted using Student’s t-test (GraphPad Prism software, version 5.0, Insightful Science LLC, San Diego, CA, USA). A p≤0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

pH value, total soluble solid content, and microbial growth of edible bird’s nest water kefir during fermentation

During the fermentation process, pH values dramatically dropped from 5.0 at the initial time of fermentation (D0) to approximately 2.5 at day 8 of fermentation (D8), indicating robust fermentation activity in EBN water kefir (Figure 2A). The observed decrease in pH in our study is consistent with results from other substrates fermented with water kefir, which is due to the microbial production of organic acids such as lactic acid, acetic acid, gluconic acid, citric acid, and butyric acid [Chomphoosee et al., 2025; Lee et al., 2025; Tireki, 2022]. These organic acids play a crucial role in water kefir by imparting a balanced tangy flavor, extending shelf life, and potentially inhibiting harmful gut bacteria through their antimicrobial effects [Lee et al., 2025]. Conversely, in the water kefir control (control 1), where EBN was replaced with water, pH levels did not decrease significantly during fermentation (Figure 2A). This is likely due to the limited nutrient availability, which slowed microbial activity and subsequent organic acid production.

Figure 2

(A) pH value, (B) total soluble solid content (°Brix), and (C) microbial growth of edible bird’s nest (EBN) water kefir and control 1 (EBN replaced with water) during fermentation. Each data point is presented as mean ± standard deviation (n=3). Asterisks indicate significant differences between water kefir at the fermentation time point and on day 0 determined by Student’s t-test at p≤0.05 (*), p≤0.01 (**) or p≤0.001 (***). LAB, lactic acid bacteria; AAB, acetic acid bacteria.

In contrast to pH, the total soluble solid content changed minimally over the fermentation period. At the start of fermentation, the content of total soluble solids was already low (approximately 1.3ºBrix) because sugar was not added to the medium in our experiment. During fermentation, there was a slight decrease of about 0.2ºBrix, reaching 1.1ºBrix at day 6 and day 8, while no change was observed in the water kefir control sample (Figure 2B). The reduction in total soluble solid content in EBN water kefir was consistent with a previous observation, which showed a decrease from 1.5ºBrix to 1.2ºBrix during whey protein fermentation with water kefir [Alrosan et al., 2023]. Catalytic metabolism of the protein components may be a factor contributing to the decrease in total soluble solids in both fermented products. In EBN water kefir, the degradation of amino acids and minerals in EBN during fermentation could also contribute to this reduction [Gong et al., 2025]. The low total soluble solid content in EBN water kefir suggests that it could be beneficial for individuals seeking to reduce their sugar intake.

Regarding microbial growth, the populations of LAB and yeast in EBN water kefir increased after 2 days of fermentation, while AAB rose after 6 days, indicating that EBN provides sufficient nutritional content to support microbial activity (Figure 2C). It is plausible that, in a low-sugar medium, yeasts initially degrade glycoproteins in EBN by enzymatically breaking down glycans from the protein core [Hirayama et al., 2019]. The sugars released from these glycans then serve as a carbon source for LAB. Additionally, LAB secrete proteinases to hydrolyze proteins into peptides, which are transported into their cells for further breakdown into amino acids [Raveschot et al., 2018]. Ethanol and lactic acid, produced as secondary metabolites from yeast and LAB fermentation, are utilized by AAB, leading to a delayed increase in AAB populations compared to yeasts and LAB [Yassunaka Hata et al., 2023]. The pattern of microbial growth varies depending on the substrate’s composition. For example, in soy whey water kefir, LAB, AAB, and yeasts increased after 2 days and remained relatively stable up to day 4 [Tu et al., 2019]. Conversely, in whey protein water kefir, all microbial populations rose at day 2, but yeast populations declined by day 4 [Alrosan et al., 2023]. Despite these differences, the interactions among microorganisms across all substrates enable coexistence and collective functioning [Tu et al., 2019]. In contrast, in the water kefir control, populations of LAB and AAB decreased over prolonged fermentation, while yeasts initially declined during the first 6 days but showed a slight resurgence at day 8, likely due to their ability to utilize bacterial byproducts as nutrients in a nutrient-deprived environment (Figure 2C).

Antioxidant capacity of edible bird’s nest water kefir

Free radicals, including hydroxyl radical, superoxide anion radical, nitric oxide radical, and peroxynitrite radical, are independently existing molecular species with unpaired electrons. They are unstable and rapidly attack lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, leading to cell damage and disruption of homeostasis [Lobo et al., 2010]. While free radicals are essential for cell signaling and immune defense, excessive levels can be detrimental, resulting in oxidative stress and contributing to cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, cancer, and inflammatory diseases [Srivastava & Kumar, 2015]. Therefore, antioxidant agents, particularly those derived from natural foods that can scavenge free radicals, have attracted significant attention for their potential in preventing and treating free radical-related health issues. Given that the free-radical scavenging capacity has been demonstrated in many water kefir products, we aimed to investigate this property in EBN water kefir [Chomphoosee et al., 2025; Gökırmaklı et al., 2025].

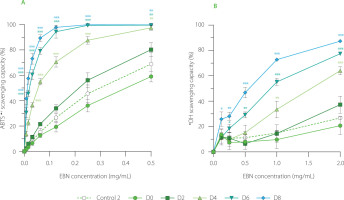

Both ABTS•+- and •OH-scavenging assays indicated that fermenting EBN with water kefir enhanced its antioxidant capacity (Figure 3). The EBN control (control 2) and non-fermented control (D0) removed approximately 35%–45% of ABTS•+ radicals at a concentration of 0.25 mg/mL of initial EBN, and 10%–15% of •OH radicals at a concentration of 1 mg/mL. In contrast, EBN fermented for 2 (D2), 4 (D4), 6 (D6), and 8 (D8) days showed significant increases in scavenging capacity, with ABTS•+ radical inhibition rising to 55%, 85%, and 100%, and •OH radical inhibition to 18%, 35%, 55%, and 75%, respectively. The pattern of increasing free radical-scavenging capacity during fermentation with water kefir was similar to the trends observed in coffee cherry and red beetroot juice water kefirs [Chomphoosee et al., 2025; Wang & Wang, 2023].

Figure 3

(A) ABTS•+-scavenging capacity and (B) •OH-scavenging capacity of edible bird’s nest (EBN) water kefir and control 2 (EBN without starter culture) during fermentation. Each data point is presented as mean ± standard deviation (n=3). D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8; EBN water kefir at day 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 of fermentation, respectively. Asterisks indicate significant differences between EBN water kefir and control 2 at each test concentration determined by Student’s t-test at p≤0.05 (*), p≤0.01 (**) or p≤0.001 (***).

The enhancement of the antioxidant capacity of EBN can be attributed to the production or release of phenolic compounds, exopolysaccharides, and bioactive peptides during fermentation with water kefir, as these bioactive substances are recognized as key free-radical scavengers in kefir products [Chomphoosee et al., 2025; Hasheminya & Dehghannya, 2020]. Chomphoosee et al. [2025] suggested that the ability of coffee cherry water kefir to inhibit free radicals may be linked to higher levels of phenolic acids, including hydroxycinnamic acids and hydroxybenzoic acids. In a study by Hasheminya & Dehghannya [2020], kefiran, a water-soluble polysaccharide, was capable of inhibiting over 70% of DPPH radicals at a low concentration of 0.8 mg/mL, indicating its effectiveness as a free-radical scavenger. Additionally, bioactive peptides have also been proposed as active contributors to the free radical-scavenging property of milk kefir [Malta et al., 2022]. It would be worthwhile to identify specific bioactive compounds responsible for the antioxidant activity of EBN water kefir in future investigations.

Water kefir intake has shown antioxidant effects in a mouse model. In a study by Kumar et al. [2021], mice given 2.5 mL/kg/day of water kefir exhibited no signs of toxicity, behavioral changes, or adverse effects, while displaying elevated levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD), enhanced ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP), and decreased nitric oxide (NO) levels in brain and kidney tissues. Similarly, Falsoni et al. [2022] found that pretreatment with water kefir provided gastroprotection against HCl/ethanol-induced ulcers in mice by reducing protein oxidation and boosting the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and catalase. These findings suggest that further in vivo research into the antioxidant properties of EBN water kefir could reveal its potential health benefits.

Anti-tyrosinase activity of edible bird’s nest water kefir

Tyrosinase is the key enzyme responsible for melanin synthesis, which determines the coloration of skin, hair, and eyes [Qian et al., 2020]. Inhibiting tyrosinase is valuable in the cosmeceutical sector for skin whitening and addressing melanin-related skin issues such as freckles, melasma, age spots, as well as certain skin cancers [Kim & Uyama, 2005]. In addition, tyrosinase inhibitors are relevant for the food industry to prevent enzymatic browning of fruits [Peng et al., 2023]. Although the anti-tyrosinase activity has been documented in various fermented broths, reports on water kefir are scarce [Abd. Razak et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2012]. This led us to investigate this property in EBN water kefir.

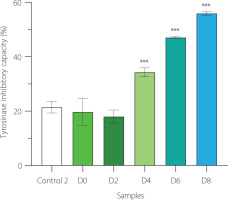

Our findings showed that at day 2 of fermentation, the ability of EBN water kefir to suppress tyrosinase was comparable to that of EBN (control 2) and unfermented EBN (D0), reducing activity by about 20% (Figure 4). As fermentation time extended beyond day 2, the anti-tyrosinase effect significantly increased, reaching approximately 55% inhibition at day 8. This indicates that fermenting EBN with water kefir enhances its capacity to inhibit tyrosinase.

Figure 4

Anti-tyrosinase activity of edible bird’s nest (EBN) water kefir and control 2 (EBN without starter culture) during fermentation. Each data bar is presented as mean ± standard deviation (n=3). D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8; EBN water kefir at day 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 of fermentation, respectively. Asterisks indicate significant differences between EBN water kefir and control 2 determined by Student’s t-test at p≤0.05 (*), p≤0.01 (**) or p≤0.001 (***).

In fermented products, phenolic compounds are key components contributing to tyrosinase inhibition. The contents of total phenolics and total flavonoids increased from 10.1 mg/mL and 9.7 μg/mL, respectively, in non-fermented red ginseng to 14.3 mg/mL and 133.2 μg/mL in the fermented version [Lee et al., 2012]. Likewise, fermented broken rice after 18 days contained over 130 times more total phenolics than its non-fermented counterpart [Abd. Razak et al., 2021]. These increases correlate with stronger tyrosinase inhibitory activity observed in both fermented red ginseng and broken rice [Abd. Razak et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2012]. Certainly, the potent anti-tyrosinase activity of our EBN water kefir may also result from the production or release of phenolic compounds during fermentation.

Research has shown that tyrosinase inhibitors decrease melanin production by directly interacting with tyrosinase through four different mechanisms: binding to the free enzyme to prevent substrate attachment at the active site (competitive mechanism); binding exclusively to the enzyme-substrate complex (uncompetitive mechanism); binding to both the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex (mixed mechanism); or binding to the free enzyme and the enzyme-substrate complex with equal affinity (noncompetitive mechanism) [Panzella & Napolitano, 2019]. Additionally, a tyrosinase inhibitor may also lower melanin synthesis by modulating the expression of genes involved in melanogenesis, especially the key regulator microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) [Yu et al., 2022]. Given that EBN water kefir in our study demonstrates tyrosinase inhibitory activity, it would be valuable to explore its specific mechanism of action on tyrosinase and its influence on the molecular pathways governing melanogenesis in future research.

Effect of edible bird’s nest water kefir on the growth of L. acidophilus and L. lactis

The potential of EBN water kefir to promote the growth of probiotics was evaluated using L. acidophilus ATCC 4356, a wellknown lactic acid bacterium that supports human gut health and two probiotic potential strains, L. lactis VCL.1 and VCL.2, isolated from Chinese cabbage Brassica rapa subsp. Pekinensis [Sarikhani et al., 2018; Vu-Quang et al., 2024]. Our experiments revealed notable differences between control groups (water kefir control (control 1), EBN (control 2), water (control 3), and nonfermented EBN (D0)) and fermented EBN at day 2 (D2), 4 (D4), 6 (D6), and 8 (D8) (Figure 5). These results suggest that EBN fermentation with water kefir enhances the viability of L. acidophilus and L. lactis, potentially contributing to improved host health. It is also worth noting that a slight increase in the bacterial growth was detected in the EBN (control 2) sample, indicating that it contains ingredients capable of stimulating the growth of L. acidophilus. In EBN, this intrinsic property is likely due to the presence of protein-attached glycan chains, which have been shown to foster the growth of probiotics such as Bifidobacteria and Bacteroides-Prevotella, while also inhibiting key pathogens like Clostridium histolyticum [Babji & Daud, 2021; Daud et al., 2019].

Figure 5

The ability of edible bird’s nest (EBN) water kefir to promote the growth of (A) Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356, (B) Lactobacillus lactis VCL.1, and (C) Lactobacillus lactis VCL.2. Control 1, water kefir control; control 2, EBN without starter culture; control 3, water; D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8, EBN water kefir at day 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 of fermentation, respectively. OD600, optical density at 600 nm. Asterisks indicate significant differences between EBN water kefir and control 3 at each time point determined by Student’s t-test at p≤0.05 (*), p≤0.01 (**) or p≤0.001 (***).

The increased activity of promoting the growth of L. acidophilus and L. lactis observed in EBN through water kefir fermentation may be attributed to bioactive compounds released during the process, including exopolysaccharides and phenolics. In a study by Tan et al. [2022a], Lactobacillus satsumensis strains isolated from water kefir grains were shown to produce α-glucan exopolysaccharides. When hydrolyzed polysaccharides by these strains are combined with kefir probiotics in synbiotic formulations, they can further enhance health benefits by promoting the growth of Bacteroidetes and increasing the production of beneficial short-chain fatty acids such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate [Tan et al., 2022a].

Phenolics with prebiotic potential have not yet been identified in water kefir samples; however, their contribution to this property should be taken into account, as they have been indicated in fermented foods [Yang et al., 2023]. In one study, Budryn et al. [2019] found that fermentation of legume sprouts with lactic acid bacteria significantly increased the content of isoflavones and the number of lactic acid bacteria while decreasing the number of molds and pathogenic bacteria. In another study by Zhou et al. [2021], polyphenols from Fu brick tea, a post-fermented dark tea, were shown to attenuate gut microbiota dysbiosis in high-fat diet-fed rats by improving key intestinal microbes such as Akkermansia muciniphila, Alloprevotella, Bacteroides, and Faecalibaculum, as well as reducing intestinal oxidative stress, inflammation, and enhancing the integrity of the intestinal barrier [Zhou et al., 2021]. Overall, our study emphasizes the potential of EBN water kefir to promote the growth of L. acidophilus and L. lactis, highlighting its promise as a prebiotic candidate for further investigation on human gut microbiota.

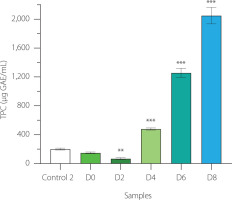

Total phenolic content in edible bird’s nest water kefir

In our study, EBN (control 2), non-fermented and 2-day fermented EBN exhibited low total phenolic contents (TPC) of approximately 50-200 μg GAE/mL. As fermentation progressed beyond 2 days, the TPC significantly increased to 500; 1,300; and 2,100 μg GAE/mL at day 4, 6, and 8 of fermentation, respectively (Figure 6). The TPC levels in EBN water kefir were higher than those in vegetable water kefirs but lower than in coffee cherry water kefir, likely due to differences in the types and amounts of phenolic compounds present in the fermenting substrates [Chomphoosee et al., 2025; Corona et al., 2016]. The upward trend in TPC during fermentation closely mirrored the increases in antioxidant activity, anti-tyrosinase, and prebiotic effects observed in EBN water kefir, suggesting these biological properties may be associated with the phenolic compounds present.

Figure 6

Total phenolic content (TPC) in edible bird’s nest (EBN) water kefir and control 2 (EBN without starter culture) during fermentation. Each data bar is shown as mean ± standard deviation (n=3). D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8; EBN water kefir at day 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 of fermentation, respectively. GAE, gallic acid equivalent. Asterisks indicate significant differences between EBN water kefir and control 2 determined by Student’s t-test at p≤0.05 (*), p≤0.01 (**) or p≤0.001 (***).

Higher phenolic levels in fermented foods are often due to enzymatic activity from microorganisms, such as tannases, esterases, phenolic acid decarboxylases, and glycosidases, which facilitate the biotransformation of phenolic compounds into more bioactive molecules [Yang et al., 2023]. For example, in coffee cherry fermentation with water kefir, chlorogenic acid, which is formed by an ester bond between caffeic acid and quinic acid, may be hydrolyzed by microbial cinnamic esterase into caffeic acid and quinic acid. Furthermore, caffeic acid can be converted into ferulic acid via the phenolic acid biosynthetic pathway. Since ferulic acid exhibits superior free radical scavenging activity compared to chlorogenic acid, its formation in coffee cherry water kefir could partly explain the enhanced antioxidant capacity of this beverage [Chomphoosee et al., 2025; Yang et al., 2023]. In a similar scenario, during EBN fermentation with water kefir, microbial metabolism of phenolic compounds may lead to increased TPC levels, which likely contribute to the improved antioxidant, anti-tyrosinase, and prebiotic properties of the fermented product.

Protein profile of edible bird’s nest water kefir during fermentation

EBN contains a majority of proteins that microorganisms in water kefir grains can metabolize to produce bioactive compounds. Therefore, we examined how the protein composition of EBN changes during fermentation. SDS-PAGE analysis revealed that EBN is rich in proteins with molecular weights exceeding 10 kDa, with those over 34 kDa being predominant (Figure 7). After 2 and 4 days of fermentation, a significant reduction in EBN proteins was observed, likely due to microorganisms consuming these proteins as sources of carbon and nitrogen. Notably, smaller molecules with molecular weights less than 10 kDa appeared at day 6 and 8 of fermentation, indicating the formation of small proteins and peptides over extended fermentation periods.

Figure 7

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis showing the protein profile of edible bird’s nest (EBN) water kefir during fermentation. D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8; EBN water kefir at day 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 of fermentation, respectively.

Lactobacillus bacteria require certain amino acids from their environment to grow. To acquire these, they produce cell envelope proteinases (CEPs) that break down proteins into peptides. These peptides are released into the fermentation medium and then transported into the bacteria, where internal peptidases further degrade them into amino acids [Raveschot et al., 2018]. The presence of various Lactobacillus species capable of producing bioactive peptides, such as L. casei, L. paracasei, L. plantarum, and L. kefiranofaciens, in water kefir grains suggests that these bacteria can hydrolyze EBN proteins and release peptides into the extracellular [Moretti et al., 2022; Raveschot et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2024]. Since bioactive peptides derived from fermented products are known to have antioxidant properties, the generation of peptides during the fermentation of EBN water kefir may contribute to enhancing its antioxidant activity [Raveschot et al., 2018].

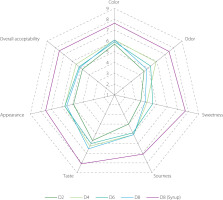

Sensory characteristics of edible bird’s nest water kefir during fermentation

Sensory evaluation plays a vital role in understanding how consumers perceive a product through their senses. These assessments offer valuable insights for product development, quality assurance, and marketing strategies, ultimately affecting consumer acceptance and purchasing choices [Ruiz-Capillas & Herrero, 2021]. Since EBN water kefir was reported for the first time in our study, we conducted tests on EBN water kefir at various fermentation durations and specifically on the 8-day fermented product sweetened with rose syrup, using a 9-point hedonic scale to evaluate color, odor, sweetness, sourness, taste, appearance, and overall acceptability [Nguyen et al., 2025a].

Among the samples tested, the EBN water kefir fermented for 2 days (D2) received the lowest scores across all attributes, primarily due to its lack of insufficient sourness and sweetness. The samples fermented for 4, 6, and 8 days (D4, D6, and D8) scored around 6.0 for color, sourness, taste, and appearance, indicating a “like slightly” response from tasters. The weakest aspect among these three was sweetness, which was linked to their very low sugar levels (Figure 2). To enhance the sensory qualities, especially given that D8 exhibited superior bioactive properties, we added rose syrup to the D8 sample to reach a final concentration of 10%, resulting in a total sugar content of approximately 8.6ºBrix. After sweetening, the sample was rated as “like much” across all characteristics (Figure 8).

Figure 8

Sensory attributes of original and syrup-sweetened edible bird’s nest (EBN) water kefir. D0, D2, D4, D6, and D8; EBN water kefir at day 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 of fermentation, respectively.

Previous studies have indicated that water kefir produced from various substrates can elicit different consumer preferences. For example, drinks made from pomegranate and rosehip juices were highly favored, while those from cherry, hawthorn, and red plum juices only received general approval [Gökırmaklı et al., 2025; Ozcelik et al., 2021]. In our research, the original EBN water kefir was regarded as moderately acceptable. Due to its higher levels of phenolic compounds, bioactive peptides, and enhanced antioxidant, anti-tyrosinase, and prebiotic properties compared to traditional boiled EBN, it may attract consumers looking for functional beverages with minimal sugar content. When enriched with rose syrup, the EBN water kefir was notably more preferred (Figure 8). This suggests promising potential for further development of EBN water kefir into a functional drink that meets the preferences of most consumers.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study is the first to demonstrate a novel EBN water kefir with enhanced abilities to scavenge free radicals, inhibit tyrosinase activity, and promote the growth of L. acidophilus ATCC 4356 and L. lactis VCL.1 and VCL.2, particularly after 8 days of fermentation. The fermentation process also increased total phenolic content and generated bioactive peptides. Evaluation tests indicate that the EBN water kefir at day 8 of fermentation achieved a “likely like” overall acceptability, while syrup-sweetening can further enhance the sensory attributes of the fermented product to “like very” on the evaluation scale. This underscores the potential of EBN water kefir as a functional beverage rich in healthpromoting compounds. Additionally, the research presents a sustainable approach to reducing EBN usage compared to traditional methods while still producing a product with high nutraceutical values. This facilitates the future development of a commercial EBN water kefir beverage that is more affordable and accessible globally.