ABBREVIATIONS

ADI, acceptable daily intake; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; BHA, butylated hydroxyanisole; BHT, butylated hydroxytoluene; CFU, colony forming units; CGMCC, China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center; CMCC, China Medical Culture Collection; DMAPP, dimethylallyl diphosphate; EFSA, European Food Safety Authority; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; FSE, freeze-dried aqueous stevia extract; FSSAI, Food Safety and Standards Authority of India; GRAS, Generally Recognized As Safe; HT-29/MTX, Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line HT-29 adapted to methotrexate; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IPP, isopentenyl diphosphate; JECFA, Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives; MEP, methyl-d-erythritol phosphate; Reb A, rebaudioside A; SCF, Scientific Committee on Foods; SPF BALB/c, specific pathogen free bagg albino laboratory-bred mouse, subline c; TPC, total phenolic content; TI, time intensity; TDS, temporal dominance of sensations; TMA, trimethylamine; VFA, volatile fatty acid; WHO, World Health Organization.

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) strongly recommends that both adults and children limit their intake of free sugars to less than 10% of their total daily energy intake [WHO, 2015]. This recommendation aligns with a growing trend among consumers, who have become more aware of their dietary choices and increasingly seek healthier and more functional food products [Bimbo et al., 2017]. The current trend in the food industry emphasizes the development of low-calorie, functional products and the incorporation of natural bio-preservatives, particularly in beverages, confectionery, and dairy items [Miele et al., 2017]. Growing attention is being paid to reducing the sugar content and the use of synthetic additives in food products, largely due to the health concerns associated with synthetic antioxidants such as butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), as well as artificial sweeteners like aspartame and saccharin [Chen & Hou, 2024; Debras et al., 2022, 2023; Mika et al., 2023]. This increasing demand for natural alternatives has highlighted stevia as one of the most promising sweeteners, owing to its dual role as a sugar substitute and as a source of beneficial nutrients, including minerals, vitamins, and antioxidants [Gerdzhikova et al., 2018; Leszczyńska et al., 2021; Muanda et al., 2011]. Several studies have reported that stevia extracts exhibit various health-promoting properties [Peteliuk et al., 2021], and strong antioxidant activity [Nuryandani et al., 2024]. In addition, stevia displays antibacterial activity, which can inhibit the growth of certain pathogenic bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [Myint et al., 2023]. Due to the growing trend in the consumption of probiotic and prebiotic products, as well as low-calorie dairy foods [Mahato et al., 2020; Narayana et al., 2022], stevia has emerged as a promising natural sweetener that can replace sugar in sweetened dairy products, with the added benefit of potential bio-preservative properties and a positive impact on intestinal well-being.

WORLDWIDE USE OF STEVIA

In 1941, stevia became known in Britain, where the plant was proposed as a sugar substitute during wartime shortages, however, it failed to gain wide acceptance, in part because of its licorice-like taste [Chesterton & Yang 2016]. The first commercialization of steviol glycosides as a sweetener dates back to 1971 by the Japanese company Morita Kagaku Kogyo. At that time, few people were interested in stevia [Rai & Han, 2022]. In 2007, stevia accounted for 40% of the intense sweeteners market in Japan, with an annual consumption estimated at 200 tonnes [Rajasekaran et al., 2007]. In recent decades, cultivation of S. rebaudiana has developed in many countries namely; Paraguay, Brazil, Uruguay, Central America, China, Thailand, and India. The area under stevia cultivation has therefore increased from an estimated 20,000–25,000 ha in 2008 to 67,000–80,000 ha in 2011. Other countries are experimenting with commercial crops such as Canada, New Zealand, Australia and in Europe: Belgium, Germany, England, France, Italy, and Greece [Gautam et al., 2022]. For more than ten years, stevia has been consumed in several countries such as Japan, China, Brazil, Korea, and the United States, and no significant adverse effects associated with its consumption have been reported [EFSA, 2022; Singh et al., 2024].

STEVIA REBAUDIANA (BERTONI) AND STEVIOL GLYCOSIDES

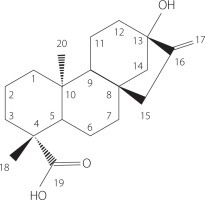

Stevia rebaudiana (Bertoni) is a perennial herbaceous plant of the Asteraceae family, native to Paraguay (South America). Stevia leaves produce diterpene glycosides called steviol glycosides, which are up to 450 times sweeter than sucrose [Peteliuk et al., 2021]. The precursor to steviol glycosides is ent-13-hydroxykaur-16-en-19-oic acid, more commonly known as steviol (Figure 1). Its biosynthesis begins in the chloroplasts from pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate until the formation of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), which ends with the methyl-d-erythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway [Moon et al., 2020]. Steviol is an aglycone from the family of tetracyclic diterpenes. In structure of steviol glycosides, carbohydrate residues can be bounded to the steviol backbone at two positions, at the C13 by an O-glycosidic bond and at the C19 by an ester-type bond. The action of glycosyltransferases on the steviol backbone allows the addition of one or more rhamnose or glucose units at each position, resulting in ten main steviol glycosides, including stevioside, rebaudiosides A, B, C, D, E and F, dulcoside A, steviolbioside, and rubusoside, although their derivatives have also been identified [Molina-Calle et al., 2017]. These glycosides are present in different proportions in the plant, and their content varies depending on the plant genotype, growing conditions, and harvesting time [Pacifico et al., 2017; Dyduch-Siemińska et al., 2020]. Stevioside and rebaudioside A are the most abundant steviol glycosides in S. rebaudiana leaves, with stevioside generally predominating [Leszczyńska et al., 2021]. In turn, rebaudioside A is recognized as the sweetest compound [Wang et al., 2022]. Other rebaudiosides (B–F) and dulcoside A occur in lower amounts [Dyduch-Siemińska et al., 2020; Leszczyńska et al., 2021; Pacifico et al., 2017].

SAFETY ASPECTS AND LEGISLATION

Over the past 50 years, numerous biological and toxicological studies have been conducted on the steviol compounds in stevia [Brusick, 2008; Peteliuk et al., 2021]. The safety of steviol glycosides has been evaluated over several decades by various regulatory bodies. The European Commission’s Scientific Committee on Foods (SCF) first reviewed this natural sweetener in 1985 and again in 1999, noting concerns regarding the absence of standardized purity criteria [SCF, 1999]. Subsequently, the Joint Food and Agriculture Organization and World Health Organization (FAO/WHO) Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) introduced provisional purity specifications in 2004, which were later finalized as permanent standards. In 2008, JECFA set an acceptable daily intake (ADI) of 4 mg per kg of body weight per day for purified steviol glycosides and confirmed their safe use as sweeteners in various foods and beverages [JECFA, 2008]. Table 1 summarizes the authorized proportions of steviol glycosides used in some food products.

Table 1

Maximum doses of steviol glycosides (E960) for use in certain food products [European Commission, 2011].

Steviol glycosides received generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status in 2008 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [FDA, 2008]. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that steviol glycosides pose no genotoxic or carcinogenic risk and are suitable for use as additives in foods and beverages. In the same assessment, EFSA established an ADI consistent with that set by JECFA, reaffirming the safety of these diterpene glycosides [EFSA, 2010]. In 2011, the European Commission added steviol glycosides as E-960 to the list of authorized sweeteners in the European Union and described the conditions of use. The stevia, whole plant and dried leaves, is then considered as “novel food” [European Commission, 2011]. Thereafter, the FDA, the SCF, and the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) also recommended using stevia as a sweetener in some food products with restricted ADI [FDA, 2008; FSSAI, 2015; SCF, 1999].

Food manufacturers are then increasingly interested in the development of food products containing stevia, especially since the use of synthetic sugars, such as aspartame, saccharin, neotame, acesulfame-K, and sucralose, has been restricted due to their several health hazards [Chen & Hou, 2024; Debras et al., 2022, 2023].

APPLICATION AND STABILITY OF STEVIOL GLYCOSIDES IN FOOD PRODUCTS

Nowadays, there are many brands of stevia-based products available in the market. Steviol glycosides are generally used as hypocaloric sweeteners and flavor enhancers in a variety of products and beverages, such as tea beverages, carbonated soft drinks, fruit juices and nectars, jams, jelly candy, chewing gum, and dairy products such as ice cream, yoghurts and milkshakes [Schiatti-Sisó et al., 2023]. Owing to their thermostability and non-fermentable properties, these compounds are frequently incorporated into baked and cooked foods [Rai & Han, 2022]. In Japan, stevia has been used for several decades in a variety of foods and beverages, including soft drinks, confectionery, pickled vegetables, and seafood products [Koyama et al., 2003]. Major beverage companies such as The CocaCola Company and PepsiCo have introduced stevia-sweetened products (for example, CocaCola Life and SoBe Lifewater) as part of their portfolio in reducedcalorie beverages [Rai & Han, 2022]. Mogra & Dashora [2009] evaluated the amount of stevia extract, prepared by boiling stevia leaf powder in water, necessary to achieve a sweetness level comparable to that of sugar. They concluded that 1.5 mL of extract per 100 mL of liquid equates to the sweetness of 5 g of sugar. The extract was subsequently applied as a sugar substitute in products including milk, coffee, tea, milkshakes, yoghurt, lemon water, and custard. Their results revealed that products containing stevia were more acceptable than the other tested products that contained artificial sweeteners. Besides, the members of the panel gave the highest sensory acceptance scores to products containing stevia (7.67–7.90). These findings indicate the real potential of stevia to be used in a large panel of food products as a sugar substitute delivering similar physical and sensory properties and providing beneficial health effects for consumers.

Steviol glycoside preparations are crystalline, odorless powders that are white or slightly yellowish. They are soluble in water and alcohol. The solubility of stevioside is 1.25 g/L and that of rebaudioside A is 3.5 g/L [Celaya et al., 2016]. They can be easily extracted with aqueous solvents. These compounds are stable in acidic solutions and at pH values ranging from 2 to 10. They do not interact with any other food ingredients and do not cause browning [Jooken et al., 2012; Kroyer, 1999]. Steviol glycosides remain chemically stable for at least one year when stored as a dry powder under ambient conditions [Prakash et al., 2014]. The high thermal stability of steviol glycosides has been demonstrated in various food matrices, including baked goods, where they remain largely intact even at elevated processing temperatures [Jooken et al., 2012]. Unlike sugar, which caramelizes at approximately 150–160°C, steviol glycosides can withstand temperatures of up to 200°C [Jooken et al., 2012].

STEVIA AND STEVIOL GLYCOSIDES IN DAIRY PRODUCTS

Steviol glycosides extracted from the leaf of S. rebaudiana have great potential to be used as a natural sugar substitute in dairy products [Mahato et al., 2020]. According to Tate & Lyle’s consumer survey [Lyobumirova, 2022], there is significant potential to attract young consumers with great-tasting, low-calorie formulations using stevia, as many perceive dairy products to be too high in fat and sugar. Among these young consumers, 77% who had reduced their dairy intake reported that they would be willing to increase consumption if healthier dairy options were available. The same survey also revealed that, between 2019 and 2021, 61% of newly launched dairy products containing stevia were yoghurts. Narayana et al. [2022] revealed that replacing 100% of sugar is possible with stevia extract for the production of vanilla flavoured set yoghurt, and concluded that among the natural alternative sweeteners, stevia is one of the promising ones. Indeed, it has been reported that adding stevia in the manufacture of dairy products enhances product quality. Muenprasitivej et al. [2022] demonstrated that the incorporation of steviol glycosides into ice cream formulations significantly improved sensory properties such as texture, flavor, and overall acceptability, while Akalan et al. [2024] showed that instant stevia powder can be successfully applied to yoghurt and other dairy products, contributing to better consistency and taste.

Steviol glycosides are highly stable in dairy products, as confirmed by Jooken et al. [2012], who observed no detectable degradation of steviol glycosides in different dairy products (including semi-skimmed milk, whole and skimmed yoghurt, and ice cream) stored under relevant conditions; their recoveries were between 96% and 103%. Similarly, Kim et al. [2021] reported recoveries ranging from 83.6% to 104.8% in non-fermented milk and 84.7% to 103.9% in fermented milk after spiking with steviol glycosides. In 2019, de Carvalho et al. [2019] conducted a study in which they used freeze-dried aqueous stevia extract (FSE) to produce stevia-fortified yoghurts. The results revealed that throughout the 30 days of cold storage, the addition of FSE to the formulated yoghurts did not affect the survival of the strains Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in comparison with the control. Furthermore, the pH, acidity and syneresis were not affected by the addition of FSE in the yoghurt’s matrix. The results also showed that during 30 days of storage, stevia-fortified yoghurt samples showed a higher total phenolic content (TPC) and a higher antioxidant activity than the control yoghurt. Moreover, during simulated gastrointestinal conditions, the yoghurt matrix preserved its TPC and antioxidant capacity. Finally, stevia-fortified yoghurt has shown great potential as a dairy functional food, improving both the antioxidant properties and TPC of yoghurt, not only during storage but also in simulated gastrointestinal conditions.

Ribeiro et al. [2020] conducted a study in which they used different stevia mix for formulation of high protein plain yoghurt. They concluded that the formulation comprising 55% of stevia 1 (75% rebaudioside A + stevioside), 5% of stevia 2 (95% rebaudioside A), and 40% of stevia 3 (50% rebaudioside A), was the best. This mix presented sensory characteristics similar to those of sucrose and sucralose in the yoghurts and had the lowest mixture development cost. Alizadeh et al. [2014] tested several ice cream formulations by replacing part of the sugar with stevia purified to 90%. Their study showed that stevia can successfully serve as a natural alternative to sucrose for producing low-calorie ice cream, without altering the product’s physicochemical characteristics or sensory quality. They also highlighted that combining sucrose with stevia improved overall consumer acceptance. Among the tested formulations, the best results were obtained with a recipe containing 13.95 g of sucrose and 20 mg of stevia, incorporated into a standard mixture of 500 mL skimmed milk, 120 g cream powder, 80 g whole milk powder, 1 g emulsifier, and 0.9 g vanilla.

To better understand how sucrose can be replaced or reduced in dairy products, Medel-Marabolí et al. [2024] carried out a study assessing the temporal sensory properties of five sweeteners such as sucrose, sucralose, stevia, aspartame, and tagatose both in aqueous solutions and in yoghurt. Using the time intensity (TI) method, panelists evaluated that stevia had a distinct temporal profile compared to the other sweeteners, with a notably longer persistence of sweetness. When tested in yoghurt and evaluated through temporal dominance of sensations (TDS) and temporal acceptability by consumers, stevia (score: 5.28) and aspartame (score: 5.13) received the highest ratings on a 9-point scale, which reflects consumer preference. In solution, stevia was also characterized by the longest perceived sweetness (13 s), along with higher dominance and acceptability over time. Overall, stevia and aspartame emerged as the most preferred options among the sweeteners studied.

Stevia is valued not only as a natural sweetener but also for its nutritional and therapeutic potential. Whole leaves contain amino acids, vitamins, minerals, fiber, and phenolic compounds that provide antioxidant and bioactive benefits [Atteh et al., 2011; Leszczyńska et al., 2021; Muanda et al., 2011; Periche et al., 2014]. Thus, consuming the whole leaf allows exploiting the entire potential of its bioactive compounds. Much of this nutritional richness is lost during processing into purified steviol glycosides, which mainly provide sweetness. Nevertheless, refining stevia into these purified compounds shifts the focus from nutritional benefits to technological functionality. They serve mainly a technological role as low-calorie sweeteners, rather than providing notable nutritional value. Nonetheless, the incorporation of stevia or steviol glycosides into foods, such as dairy products, remains promising, as it can improve both the organoleptic qualities and the bioactivity of foods while serving as a natural low-calorie sweetener and antioxidant.

STEVIA EFFECTS ON LACTIC ACID BACTERIA OF DAIRY PRODUCTS

Several studies have highlighted the multifunctional role of S. rebaudiana in supporting probiotic development and gut health. Weber & Hekmat [2013] demonstrated that steviol glycosides are suitable sweeteners for probiotic yoghurts, as they do not inhibit the growth of Lacticaseibacillus strains. Similarly, Bahnas et al. [2019] reported that adding 1% stevia leaf extract to cheese whey or milk permeate-based beverages significantly enhanced the viability of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei, an effect attributed to the presence of phytochemicals and minerals. In accordance with these findings, stevioside and stevia leaf extract were found to enhance lactic acid production in Lacticaseibacillus casei, Levilactobacillus brevis, and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, according to Davoodi et al. [2016]. Tested at 0.5%, 1.0%, and 2.0% (w/v), a stevia leaf extract showed a content-dependent effect, while stevioside maintained a relatively consistent impact across all levels.

Beyond the leaves, other parts of the plant, particularly the roots, also hold promise: they contain fructans, recognized as functional prebiotic ingredients that stimulate the growth of beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Lacticaseibacillus [Sanches Lopes et al., 2016]. Thus, although root extracts are not used commercially as sweeteners, they highlight the broader nutritional and functional potential of the plant beyond its sweetening properties.

Kim et al. [2023] evaluated how supplementing fermented milk with stevia extract influences both bacterial growth and product quality. They tested different levels of stevia extract and observed that higher levels (0.5%, w/v) accelerated fermentation by stimulating the proliferation of beneficial lactic acid bacteria, particularly S. thermophilus, Lacticaseibacillus acidophilus, and Bifidobacterium longum. Stevia extract supplementation also resulted in an increase in the titratable acidity, total solid content, viscosity and water-holding capacity. In line with this, Ozcan et al. [2017] conducted a study in which a 10% commercial stevia extract was used during fermentation, resulting in improved survival of L. casei in both basal medium and fermented milk. Similarly, Dong et al. [2021] demonstrated that adding 12% (v/v) stevia extract during fermentation reduced the fermentation time (from 12 h to 9 h) and enhanced the viability of L. plantarum (8.72 log CFU/mL) under simulated gastric digestion. Ozdemir & Ozcan [2020] suggested that fermented milks containing steviol glycosides may serve as promising functional dairy products by effectively delivering probiotic bacteria.

Alizadeh [2021] explored the use of steviol glycosides for the development of probiotic mango nectar enriched with L. plantarum. Different formulations were then prepared by combining the probiotic strain (L. plantarum, 106 CFU/mL) with varying amounts of inulin (0%, 4%, and 8%, w/w) as a prebiotic texturizer, and stevia (0%, 2%, and 4%, w/w) as a natural low-calorie sweetener. The findings indicated that the formulation containing 4% (w/w) stevia and 4% (w/w) inulin not only enhanced the survival of L. plantarum over a 45-day storage period but also offered the most favorable physicochemical characteristics and sensory qualities.

In 2014, Kunová et al. [2014] explored the potential prebiotic role of steviol glycosides (2 g/L) on various Bifidobacterium and Limosilactobacillus strains. While some strains, such as B. bifidum, B. breve, B. adolescentis, and L. mucosae, showed a slight increase in growth, the overall capacity of these bacteria to metabolize steviol glycosides remained very limited, as the compounds are not fermentable. The authors concluded that a prebiotic effect could not be demonstrated, as their analysis focused exclusively on bacterial growth without considering potential metabolic outputs [Kunová et al., 2014]. More in-depth analysis of the bacterial metabolome would make it possible to detect more subtle functional modifications. In addition, only 10 bacterial genera are tested in this study, which does not reflect the true diversity of the gut microbiota. Another study conducted by Li et al. [2014] investigated the impact of Rebaudioside A (Reb A) on the growth of two probiotic strains: B. longum ATCC 15707 and L. plantarum ACCC 11095. The results showed that Reb A had no significant effect on the growth of B. longum ATCC 15707, whereas it significantly enhanced the growth of L. plantarum ACCC 11095, particularly at concentrations of 0.5% and 1%. Ozcan & Eroglu [2023] investigated the prebiotic effects of steviol glycosides on B. animalis subsp. lactis for dietetic dairy products. They used in vitro fermentation assay with basal medium (non-carbohydrate containing Man, Rogosa and Sharpe agar) supplemented with different concentration of steviol glycosides (from 0.025% to 1%, w/v) and inulin at 1%. The combination of 0.025% steviol glycosides + 1% inulin showed the highest prebiotic activity, enhancing bacterial viability and short-chain fatty acid production. While steviol glycosides alone also supported growth, the best results were seen with the combination, suggesting a synergistic effect. The study concludes that stevia, particularly with inulin, can be used as a functional sugar substitute and prebiotic for modulating gut microbiota. Rosa et al. [2021] emphasized that enriching dairy products with prebiotics can provide several health benefits, such as the improvement of intestinal well-being, anti-diabetic, and anti-hypertensive properties. They also noted that prebiotics may enhance product quality by influencing physicochemical, microbiological, and sensory properties. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of these benefits largely depends on selecting the right type and concentration of prebiotic compounds.

To classify a food ingredient as a prebiotic it must fulfil specific criteria. It has to be resistant to gastric acidity, to hydrolysis by mammalian enzymes, and to gastrointestinal absorption, it must be fermentable by intestinal microbiota; and selectively stimulate the growth and/or activity of those intestinal bacteria that contribute to health and well-being [Roberfroid, 2007]. Steviol glycosides meet some of these criteria, however more in-depth studies are necessary to confirm or refute their prebiotic effect. Moreover, most of the cited studies are performed in vitro or in animal models. Randomized clinical trials in humans are required to validate the effects on the gut microbiota and digestive physiology before drawing definitive conclusions about the potential benefits of stevia.

STEVIA EFFECTS ON BACTERIA THAT CAUSE SPOILAGE OF DAIRY PRODUCTS

Several researchers have highlighted the antimicrobial activity of stevia crude and purified extracts against a wide range of pathogenic bacteria and fungi [Chen et al., 2024; Jayaraman et al., 2008; Myint et al., 2023]. Chai et al. [2024] demonstrated that extracts of S. rebaudiana leaves fermented with L. plantarum exhibited strong antimicrobial activity against food-borne pathogens, including E. coli and S. aureus. Interestingly, these fermented extracts displayed a selective action, as they did not significantly inhibit beneficial bacteria such as Lacticaseibacillus spp. and Bifidobacterium spp., thereby underscoring their potential as natural food preservatives. This antibacterial effect was mainly attributed to secondary metabolites produced during fermentation through microbial deglycosylation and enzymatic decomposition of stevia compounds, since the unfermented aqueous extract exhibited little to no antibacterial activity. Jayaraman et al. [2008] provided evidence of the antibacterial action of stevia leaf extracts at 50 mg/mL. The acetone extract showed the strongest activity, producing inhibition zones of 19 mm against S. aureus and 18 mm against B. subtilis, indicating greater effectiveness against Gram-positive than Gram-negative bacteria. The ethyl acetate extract also inhibited V. cholerae with an 18 mm zone, whereas no activity was detected for the aqueous extract. In a subsequent study, Puri & Sharma [2011] demonstrated that purified stevioside solution at 100 μg/mL inhibited the growth of several bacterial species, including B. subtilis, B. cereus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa and S. enterica ser. Typhi. In particular, a clear inhibition zone of 12 mm was observed against B. cereus, a spoilage microorganism frequently associated with milk and dairy products, highlighting the possible use of stevioside to enhance food shelf life.

Li et al. [2014] examined how Reb A influences the growth of common foodborne pathogens. The study included two Gram-negative strains (E. coli O157:H7 and S. enterica ser. Typhimurium ATCC 13311) and two Gram-positive strains (S. aureus CGMCC 26001 and Listeria monocytogenes CMCC 54007). Their findings revealed that Reb A at 0.5% (w/v) significantly reduced the growth of S. aureus (p<0.05), with an even stronger effect (p<0.01) observed at 1.0% (w/v). By contrast, only minor inhibitory effects were detected against E. coli, S. enterica ser. Typhimurium, and L. monocytogenes. Chen et al. [2024] found that an extract from stevia containing chlorogenic acid isomers (notably isochlorogenic acid C) exhibited strong antibacterial activity against multiple strains of E. coli. The minimum inhibitory concentration was 2 mg/mL, and the bactericidal concentration was 8 mg/mL for some strains. The mechanism included damage to cell wall and membrane permeability, leakage of intracellular proteins and potassium ions, and loss of outer membrane integrity.

Based on the above results, it can be concluded that stevia extracts could be used as food additives in dairy products, as they inhibit the growth of pathogens and enhance the growth of probiotic bacteria.

METABOLISM OF STEVIOL GLYCOSIDES BY GUT MICROBIOTA AND MICROBIAL ENZYMES

The human gut microbiota contributes significantly to the host’s health by regulating metabolism and cellular immune response. Bacillota and Bacteroidota represent 90% of the dominant phyla in the intestinal flora [Rinninella et al., 2019]. However, the composition and function of the gut microbiota can be positively or negatively influenced by diet [Kasti et al., 2022; Wen & Duffy, 2017]. In this context, with the increased use of stevia as a sugar substitute, several studies have investigated the effect of its consumption on intestinal well-being [Becker et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2024].

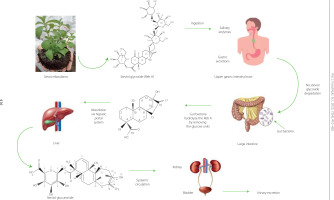

The metabolism of stevia presented in Figure 2 depends on gut microbiota and microbial enzymes that break down the steviol glycosides into steviol [Becker et al., 2020; Kasti et al., 2022]. Salivary and gastric juice enzymes, such as pancreatic α-amylase, pepsin, and pancreatin, cannot degrade steviol glycosides, these compounds pass intact through the upper gastrointestinal tract, where they are hydrolyzed by intestinal bacteria enzymes [Renwick & Tarka, 2008]. Among the bacterial group found in gastrointestinal tracts of humans and animals, Bacteroidota are primarily responsible for the hydrolysis of stevioside and rebaudioside A to steviol, whereas other bacteria, such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Clostridium, Escherichia (coliforms), and Enterococcus, were unable to hydrolyze and use steviol glycosides as a usable substrate [Kasti et al., 2022; Renwick & Tarka, 2008]. After degradation, steviol is absorbed via the portal vein and then reaches the liver, where it is metabolized to steviol glucuronide, which elicits great detoxification effects on the liver [Li et al., 2014]. Then, it is excreted in the urine [Kasti et al., 2022; Renwick & Tarka, 2008].

EFFECT OF STEVIA CONSUMPTION ON INTESTINAL MICROBIAL DIVERSITY

Total species diversity is determined by two indicators: the first one is α-diversity (the average species diversity in a particular area or habitat), and the second one is β-diversity (the diversity of species between two habitats or the measure of similarity or dissimilarity of two regions). Several studies have focused on the effect of stevia consumption on intestinal microbial diversity [Li et al., 2014; Kwok et al., 2024; Mahalak et al., 2020]. Some of these studies showed that stevia consumption has led to higher α-diversity [Li et al., 2014; Mahalak et al., 2020; Nettleton et al., 2020]. Whereas, others indicated that there are no changes in α-diversity [Nettleton et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2020]. In turn, some studies demonstrated that stevia consumption did not significantly change β-diversity [Mahalak et al., 2020; Nettleton et al., 2019, 2020]. Even if stevia consumption may affect the colonic microenvironment, it seems that this effect depends on the amount and the frequency of intake. Li et al. [2014] investigated the dose-dependent effects of rebaudioside A in an in vivo model using SPF BALB/c mice, administered at low (0.5 mg/mL) and high (5.0 mg/mL) concentrations. They found that the two concentrations did not alter the growth of enterobacteria and lactobacilli and did not affect the microbial diversity, however it could have modified the number of some bacterial genera. This study reflects some methodological limitations. The analyzed samples were relatively small (n=15 mice randomly divided into three groups) and from a single breeding stock, thereby restricting the extent to which the findings can be generalized. Moreover, the statistical significance of the observed changes in some bacterial genera was not reported. Studies with larger and more varied samples would be necessary to confirm or refute these effects.

Mahalak et al. [2020] conducted a study in which they compared the changes that occur in the gut microbiota in the feces of a healthy donor after exposure to steviol glycosides and erythritol. The findings indicated that steviol glycosides significantly increased the growth of gut bacteria. Despite this, the overall structure of the gut microbiota remained unchanged, with the Bacteroidaceae family being predominant, followed by Lachnospiraceae, Fusobacteriaceae, and Ruminococcaceae. Furthermore, other research reported that when mixed fecal bacteria from volunteers were exposed to stevioside, there was a slight inhibition of anaerobic bacteria, whereas rebaudioside A caused mild inhibition of aerobic bacteria, particularly coliforms [Gardana et al., 2003]. Further long-term studies are needed with appropriated doses and adequate subject sizes to evaluate the real effects of stevia consumption on gut microbiota.

Kim et al. [2023] investigated the effect of stevia leaf extracts on fermented milk and the health effect of this product on human colon cells. They demonstrated that stevia extract-supplemented fermented milk enhanced mucin glycoprotein production in human colon epithelial cells (HT-29/MTX). Mucin contributes to the formation of a viscoelastic gel within the mucus layer, serving as a protective barrier for the gastrointestinal tract against certain conditions, such as bacterial infections and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [Corfield, 2015]. Recently, Ma et al. [2023] demonstrated that the leaf extract of S. rebaudiana fermented with Pediococcus pentosaceus LY45 repressed trimethylamine (TMA) production. Oxidation product of TMA – trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), is recognized as a risk marker of cardiometabolic and hepatic diseases, as well as other chronic diseases [Lynch & Pedersen, 2016]. These findings suggest that fermenting stevia extracts with lactic acid bacteria could be a promising approach for generating specific metabolites that may help modulate and restore the gut microbiota.

Zhao et al. [2018] reported that dietary supplementation with stevia residue extracts in mice improved impaired glucose regulation and helped restore intestinal balance. The intervention was associated with modulation of gut microbiota composition, indicating that bioactive compounds from S. rebaudiana can influence metabolic health while supporting beneficial intestinal bacteria. These findings support the potential role of stevia extracts in maintaining gut microbial homeostasis and preventing metabolic disturbances.

STEVIA IN DAIRY ANIMALS’ FEEDING

In addition to studies on stevia-supplemented dairy products, many authors have investigated the effects of its feeding in dairy livestock. They demonstrated that stevia or its extracts may enhance productive performance and milk quality [Gerdzhikova et al., 2018]. Stevia can be used in animal feeding as both an additive and hay substitute, depending on the specific application and the type of animal being fed. Stevia hay can be used as a substitute for traditional hay in animal feeding. It provides high levels of metabolizable energy per kg of dry matter; 2,894 kcal in leaves and 2,052 kcal in stems and blossoms [Gerdzhikova et al., 2018]. It is also rich in proteins, amino acids, minerals and fibers, mainly in the stems. The metabolizable energy and fiber content of stevia stem suggest its usage oriented to ruminants rather than monogastric animals [Atteh et al., 2008, 2011]. Stevia extract, specifically stevioside, can be used as a feed additive to increase feed intake and/or growth rate in animals [Montero et al., 2016].

Stevia has been studied for its potential benefits in dairy species; sheep, goats and cows, but there is a limited research on its specific effects on milk quality. The introduction of stevia straw, which is a by-product of the stevia sugar crop, has been studied in sheep, as it is rich in nutrients and active compounds, making it a good feed material. It has been demonstrated that adding 1% (w/w) of stevia stalk to sheep rations enhanced rumen fermentation capacity, as indicated by a decrease in pH value and an increase in ammonia nitrogen concentration [Zhang et al., 2023]. In goats, Han et al. [2019] showed that the supplementation of basal diet with stevioside did significantly affect feed intake, ruminal fermentation and digestion, and improved blood metabolites, indicating potential benefits for goat health. These studies, did not directly measure the effects of stevia on milk quality, but it is possible that the improved rumen fermentation and nutrient utilization could indirectly contribute to better milk quality [Jiang et al., 2022]. In dairy cows, the introduction of stevia hay into a diet for Holstein lactating cows to partially substitute alfalfa hay improved rumen fermentation, as demonstrated by an increase in volatile fatty acid (VFA) content, nitrogen utilization, and lactation performance [Jiang et al., 2022]. The study showed that diets supplemented with 6% and 12% (w/w) of stevia hay caused the most significant improvements in rumen fermentation and milk performance with a higher yield and fat content. Stevia may also positively affect animal products’ quality by providing antioxidants and functional nutrients.

In summary, stevia used in feeding dairy animals has many benefits and may be considered in ration formulation as it improves the feed intake, rumen fermentation, nitrogen utilization, and lactation performance. However, more research is needed to fully understand the optimal doses, the duration of supplementation and its long-term effects to improve milk quality.

CONCLUSIONS

The growing consumer demand for sugar reduction in foods has prompted the dairy industry to explore natural sweetener substitutes like stevia to reduce sugar content in their products. This review highlights the promising potential of stevia and its glycosides as sugar replacers in dairy products. Based on the above studies, fortification of dairy products with stevia can provide excellent sensory properties to the product that can promote the intestinal well-being. Stevia can act as a sweetening agent with zero calories, as an enhancer of probiotic bacteria, and as a natural bio-preservative inhibiting the growth of pathogens. However, further research is recommended to determine optimal stevia doses for specific dairy applications and to better understand its long-term impacts on human health through clinical trials. In vitro and animal studies compiled in this review demonstrate stevia’s ability to enhance growth and viability of probiotic bacteria in dairy matrices. However, elucidating the precise prebiotic mechanisms of action via human trials and gut microbiota studies could further validate stevia’s role as a functional ingredient. In addition to glycosides, stevia also offers other phytochemicals, such as flavonoids, phenolic acids, as well as fatty acids, proteins, vitamins, and minerals that contribute to the antioxidant potential and health attributes of stevia-fortified dairy products. However, controlled studies in humans are required to substantiate these functional benefits. Research is also needed to evaluate the effects of incorporating stevia extracts or stevia by-products in dairy animals’ feeding on subsequent milk yield and quality.

While long-term stevia consumption appears safe based on existing toxicological data, future research should continue assessing potential allergenicity concerns as usage increases globally. Comprehensive safety evaluation will enable greater consumer confidence in this natural sweetener. In summary, the unique nutritional and functional characteristics of stevia present opportunities for innovative dairy product development aligned with consumer preferences for natural, low-sugar, and health-promoting foods. Harnessing stevia’s multi-faceted potential through strategic research and application in dairy industry could accelerate the growth of this ingredient in the functional foods market.