INTRODUCTION

Consumer demands in the food production sector have changed dramatically in recent years. Modern consumers expect food to not only provide essential nutrients but also address nutritional deficiencies and promote well-being. Functional foods, which can be either natural or industrially processed, play a crucial role in meeting these new expectations [Alongi & Anese, 2021]. Meat, such as chicken, is a rich source of protein, omega-3 fatty acids, minerals, and vitamins. Consumption of chicken meat has increased significantly over the last few decades and is expected to rise further. Chicken meat is not only nutrient-dense but also relatively low in calories, making it an excellent choice for those seeking a healthy diet. Additionally, its mild flavor, consistent texture, and light color make it suitable for various processing methods [Petracci et al., 2013]. However, despite the nutritional benefits of chicken meat, it does have certain drawbacks. For instance, it lacks dietary fiber, and its high polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) content makes it prone to lipid oxidation, which can lead to changes in nutritional value, color, texture, and flavor [Das et al., 2020]. Furthermore, meat products, in general, have been associated with high cholesterol, obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Consequently, there is a growing interest in developing “healthier meat products” by reducing unhealthy compounds like nitrates, salt, and saturated fats, while simultaneously enhancing antioxidant capacity and preserving nutritional value [Akram et al., 2022]. Numerous recent studies have highlighted the important role of plant-derived materials and their bioactive compounds, including phenolics, in preventing lipid oxidation by neutralizing free radicals [Bai et al., 2025; de Oliveira et al., 2025]. The meat industry has recognized the protective effects of these plant-based materials, making them an appropriate choice for preserving meat products and lowering the risk of development of various human diseases [Bhat et al., 2020].

One such plant with potential health benefits is the prickly pear (Opuntia spp.), which is found in arid and semiarid regions of Latin America, the Mediterranean region, and South Africa [Sipango et al., 2022]. Prickly pear fruit (Opuntia ficus-indica L.) has gained popularity in recent years due to its nutritional and antioxidant properties. The fruit can be green, red, or purple, depending on the presence of pigments, like betalains [García-Cayuela et al., 2019]. Notably, the peel of the prickly pear fruit accounts for 30% to 50% of the total fruit, depending on the cultivar [Gómez-Salazar et al., 2022].

Fruit peels, often discarded as waste, are a valuable and cost-effective source of phytochemicals with significant functional potential. Prickly pear peels (PPP) contain cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, proteins, minerals, and antioxidants, making them suitable for various food applications [Barba et al., 2017]. Despite being considered waste in many cultures, PPP contain numerous bioactive compounds that elicit benefits to human health and can be utilized in various food products. These peels are rich in antioxidants, which protect the body from oxidative stress and free radicals. Moreover, the phenolics and betalains present in PPP have demonstrated antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer properties [Melgar et al., 2017; Reguengo et al., 2022]. Another bioactive compound found in PPP are phytosterols, which can help lower cholesterol levels and reduce the risk of heart disease [Amaya-Cruz et al., 2019; Reguengo et al., 2022]. Additionally, PPP is high in dietary fiber and vitamin C [Amaya-Cruz et al., 2019; Jiménez-Aguilar et al., 2015].

Dietary fiber, a non-starch polysaccharide that cannot be broken down and absorbed by human digestive enzymes, offers various health benefits. However, for high-fiber products to be appealing, they should also possess improved technological characteristics. With its water retention ability, lack of distinct flavor, and ability to reduce cooking loss, fiber is an excellent component for the development of meat products [Akram et al., 2022; Zaini et al., 2020].

While the use of PPP has been explored in improving pan bread quality [Anwar & Sallam, 2016], biscuit formulations [Bouazizi et al., 2020], and sustainable baker’s yeast production [Diboune et al., 2019], there is limited research on its application in processed meat products. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the impact of PPP incorporation on the quality of functional chicken sausages. The study also examined the nutritional and chemical properties of the sausages, as well as their storage stability and sensory characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Prickly pear fruits (Opuntia ficus-indica L.) were collected randomly from different plants at multiple locations from the Haifan Directorate in southern Taiz City, Yemen (latitude 13°16’06’’ N, longitude 44°18’16’’ E). Boneless chicken breast was purchased from a local supermarket in Yibin City, Sichuan, China. Ingredients for sausage formulation, including chicken skin fat, soy protein isolate, ground black pepper, and non-iodized salt, were obtained from local markets in Yibin City. All chemicals and reagents used were of analytical grade.

Prickly pear peel powder preparation

To ensure cleanliness, prickly pear fruits were thoroughly washed under running tap water to remove dust and debris. The pulp and peel were then manually separated using a knife. The separated peels were sliced into small pieces (approximately 2×2 cm2), which were then soaked in a solution of sodium hypochlorite (40 mg/L) for 30 min to reduce microbial load [Bouazizi et al., 2020]. Following this, the peels were thoroughly rinsed three times with distilled water to remove any residual hypochlorite. The rinsed PPP were then oven-dried at 40°C for 48 h using an electrothermal blast drying oven (WLG-45B, Tianjin, China). The drying process continued until the powder’s moisture content was reduced to 6.36±0.71 g/100 g. The dried peels were subsequently ground into a fine powder using a hammer mill, then sieved through a 60-mesh screen. The resulting peel powder was placed in polyethylene bags and stored at 4°C for future use.

Preparation of chicken sausages and their storage

The sausages were made with boneless chicken breast following the procedure of Manzoor et al. [2022] with a few alterations. In a bowl chopper, 1,000 g of boneless chicken breast was blended with 200 g of chicken skin fat, 20 g of soy protein isolate, 150 mL of ice water, 2 g of ground black pepper, and 10 g of non-iodized salt. These ingredients were mixed for 35 s to achieve a highly homogeneous meat batter. The prepared PPP powder was then incorporated into the meat batter at four different levels (w/w, based on the total meat batter weight): 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8%. A control sample (0% PPP) was prepared using the same method, but without PPP addition. The meat batters (both control and PPP-supplemented) were filled into cellulose casings using a sausage stuffer and labeled. The sausages were cooked in a conventional electric oven at approximately 200°C for 15 min, followed by 30 min of steaming at 75±2°C in a steamer, and then 20 min of dipping in cold water at 15°C. After draining, the sausages were placed in airtight nylon-polyethylene bags and stored at 4°C for up to 21 days. Their content of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) and microbiological quality were determined at regular intervals throughout the storage period (on days 0, 7, 14, and 21). All other parameters, including physical, chemical, and cooking properties, were measured only once on day 0.

Proximate analysis

Chemical composition of the sausages was determined using the methods recommended by AOAC International [AOAC, 2007]. The oven-drying method at 105°C was used to determine the moisture content (method no. 950.46). The protein content was determined using the Kjeldahl procedure (method no. 981.10], with the total nitrogen content multiplied by a conversion factor of 6.25. The lipid content was determined using the Soxhlet method by utilizing a solvent extraction system with petroleum ether (method no. 960.39). The total ash content was determined using an incinerator at 525°C (method no. 920.153). The carbohydrate content was calculated by subtracting from 100 the sum of moisture, lipid, protein, and ash contents expressed in g per 100 g of sausage.

Total dietary fiber analysis

The total dietary fiber (TDF) content of both the sausages and PPP powder was determined using the enzymatic-gravimetric analysis proposed by the AOAC International [AOAC, 2005]. A gram of defatted dried sample was weighed and digested with a series of enzymes. First, α-amylase was added, and the combination was heated for 15 min at 98–100°C. This was followed by the addition of protease and amyloglucosidase, and a 30-min incubation at 60°C. The residue was filtered, washed with acetone and 95% ethanol before being dried and weighed. The protein content was determined using the Kjeldahl method, and the ash content was determined by heating a similar sample to 525°C in a muffle furnace. By subtracting the weight of protein and ash from the weight of the residue, the TDF content was calculated and expressed in g per 100 g of sausage or PPP powder.

pH determination

In 50 mL of distilled water, 10 g of chicken sausages were homogenized for 30 s, and the pH of the homogenate was measured using a pH meter (Mettler Toledo FE20/EL20, Shanghai, China).

Water-holding capacity determination

The centrifugation technique was used to estimate the water-holding capacity (WHC), according to the procedure by Zhuang et al. [2007] with some modifications. A 10-g sample of sausage (wsample) was thoroughly homogenized in a laboratory blender with 15 mL of a 0.6 M NaCl solution. The mixture was then centrifuged at 3,000×g and 4°C for 15 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was carefully discarded, and the remaining residue was weighed (wresidue). The WHC was calculated using Equation (1):

Cooking yield determination

To assess the cooking yield, the sausages were weighed before (winitial) and after (wfinal) the complete three-step cooking and cooling process, following the method described by Choi et al. [2014]. The cooking yield was calculated using Equation (2):

Color coordinate measurement

A Konica Minolta CR-400 chromameter (Tokyo, Japan) was applied to measure the color of sausages. Six perpendicular measurements were recorded, and photographs of various surfaces of the sausage were taken. The results were reported as CIE a* (redness), L* (lightness), and b* (yellowness). The instrument was calibrated using a standard white tile before measurements. The illuminant used was D65, and the observer angle was 10°.

Total phenolic content determination

The method with the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was used to determine the total phenolic content (TPC) of both the sausages and PPP powder, as described by Özünlü et al. [2018], with some alterations. Chicken sausages or PPP powder (1 g) were homogenized and extracted overnight at 4°C in 10 mL of methanol with continuous agitation at 180 rpm. The mixture was then centrifuged at 3,000×g for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. Then, 0.5 mL of the chicken sausage extract, 2.5 mL of the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (10-fold diluted), and 2 mL of a sodium carbonate solution (75 g/L) were combined and left for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance at 765 nm was measured using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Mapada Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), and gallic acid was used as the standard. The results were expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per 100 g of sausage or PPP powder.

Texture profile analysis

Texture profile analysis (TPA) was conducted using a TA.XT Plus texture analyzer (Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, UK) on six replicates of each sample. The cooked sausage samples were allowed to cool to room temperature before analysis [Choe et al., 2013]. Each sausage was cut into standardized cylindrical pieces measuring 20 mm in height and 25 mm in diameter. To ensure consistent and reproducible contact with the compression probe, the samples were sliced horizontally to create uniform, flat cross-sectional surfaces. A cylindrical aluminum probe was used to perform a two-cycle compression test. The pre-test, test, and post-test speeds were set at 2.0, 1.0, and 5.0 mm/s, respectively. Samples were compressed to 50% of their original height, and a trigger force of 5 g was applied. Data were collected and analyzed for hardness (N), springiness, cohesiveness, and chewiness (N).

Determination of the content of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

The content of TBARS was determined on days 0, 7, 14, and 21 following the procedure proposed by Manzoor et al. [2023] with some alterations. Chicken sausage samples (5 g) were homogenized in a blender with 25 mL of 7.5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) for 2 min. After a 10-min centrifugation at 3,500×g, the supernatant was filtered and mixed with 5 mL of a 0.02 M thiobarbituric acid (TBA) solution. The samples were then immersed in a 95°C hot water bath for 35 min. The reaction products between TBA and the oxidized substances were measured at 532 nm using a UV-1800 PC spectrophotometer (Mapada Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The TBARS values were calculated from a standard curve with 1,1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane (TEP) and presented as mg of malondialdehyde (MDA) equivalent per kg of sausage (mg MDA/kg).

Microbiological analysis

The microbial load of the chicken sausage treatments was determined on days 0, 7, 14, and 21 by estimating the total plate count using the method proposed by Akram et al. [2022]. Chicken sausage samples (1 g) were aseptically diluted in 9 mL of sterile peptone water (0.1%, w/v). The samples were homogenized using a stomacher for 60 s to ensure proper dispersion. An appropriate serial 10-fold dilutions were prepared. From these dilutions, aliquots were surface-plated onto plate count agar using the streak plate technique. The plates were then incubated aerobically at 37°C for 48 h. The findings were presented as colony forming units per g of sausage (105 CFU/g).

Sensory evaluation

A trained sensory panel consisting of 30 regular sausage consumers, all experienced in the sensory evaluation of meat products, assessed the chicken sausage samples. Panelists were selected based on their consistent consumption of sausages and their proven ability to identify and differentiate basic tastes and textures. This ability was confirmed through a series of taste and texture identification tests conducted prior to the main evaluation. Before the study, they participated in a brief training session to familiarize themselves with the specific attributes to be evaluated: appearance, color, odor, taste, hardness, juiciness, and overall acceptability. They also learned to use the seven-point hedonic scale for their evaluations. The sensory evaluation took place in individual, well-lit booths designed to minimize distractions. Samples were prepared by removing the casings, cutting the sausages into slices approximately 3 mm thick, and serving them at room temperature on white plastic plates, each randomly numbered with three-digit codes [Stajić et al., 2018]. The sausages were evaluated immediately on the first day of preparation. Three slices of each product were served sequentially in a monadic manner. Panelists used water and unsalted crackers to cleanse their palates between samples. Each attribute (appearance, color, odor, taste, hardness, juiciness) and overall acceptability were rated using a seven-point hedonic scale, defined as follows: 1 (extremely dislike), 2 (dislike), 3 (slightly dislike), 4 (neither dislike nor like), 5 (slightly like), 6 (like), 7 (extremely like).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the results were reported as mean and standard deviation. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Duncan’s multiple range test was performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to evaluate the impact of PPP on the sensory and physicochemical attributes of the chicken sausages. A significance level of p<0.05 was set to determine the differences between the means for the various attributes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Proximate composition of chicken sausages

The proximate composition of chicken sausages is illustrated in Table 1, and the results indicate that there were no significant variations (p≥0.05) in moisture, protein, or lipid content among the sausages. However, as the amount of PPP added to the meat batter increased, the ash content in sausages also significantly increased (p<0.05). This increase in ash content can be attributed to the high levels of TDF, resistant starch, and minerals in the PPP [El-Beltagi et al., 2023; Parafati et al., 2020]. The mineral content influences the ash content, indicating that the inclusion of PPP increases the nutritional value in terms of mineral content [Park et al., 2011]. Similar findings were reported by López-Vargas et al. [2014] in their study on the impact of passion fruit albedo on pork burgers and by Zaini et al. [2020] in their investigation on the influence of banana peel powder on chicken sausages.

Table 1

Proximate composition (g/100 g) of chicken sausages with different levels of prickly pear peel (PPP) powder (2–8% of the total meat batter, w/w).

The dietary fiber content of sausages

Because of a low dietary fiber content of meat, its consumption has been linked to chronic diseases. However, the inclusion of PPP in chicken sausages significantly increased the TDF content (p<0.05), as shown in Table 1. The TDF content of PPP used in this study was 31.70± 0.01 g/100 g. This high fiber content accounts for the significant increase in TDF determined in the sausages with added PPP, which ranged from 1.68 g/100 g for the control to 5.39 g/100 g for the 8% PPP sausage. The presence of fiber in the control sausage may be attributed to the other ingredients in the formulation, such as soy protein isolate and spices. The inclusion of fiber in meat products improves their health benefits. The presence of fiber in meat shortens the time it spends in the intestines, minimizing the exposure of colon cells to carcinogenic substances. Thus, the presence of fiber in meat could mitigate its carcinogenic impact [Arias-Rico et al., 2025]. Similar to our findings, Zaini et al. [2019] observed an increase in crude fiber content in fish patties when banana peel powder was added.

pH of sausages

The pH value is a crucial variable to measure as it affects the color, texture, shelf-life, and water-holding capacity of meat products. As displayed in Table 2, the incorporation of 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8% PPP to chicken sausages led to a significant decrease in pH values (p<0.05) compared to the pH value of the control sausages. Manzoor et al. [2022] reported lower pH values in chicken sausages supplemented with various levels of mango peel extract compared with the control sample, which is consistent with our findings. Furthermore, Mahmoud et al. [2017] discovered lower pH values in burgers supplemented with various amounts of orange peel when compared with the control sample. These findings can be explained by the presence of organic acids in the PPP [Tunç et al., 2025]. The reduction in pH is beneficial as it hinders microbial growth under lower pH conditions.

Table 2

The pH values and cooking properties of chicken sausages with different levels of prickly pear peel (PPP) powder (2–8% of the total meat batter, w/w).

Cooking properties of chicken sausages

WHC is a crucial quality characteristic affecting meat products’ texture and overall sensory properties. It is primarily influenced by the muscle pH and protein structure [Mahmoud et al., 2017]. Water loss poses a major concern for the meat industry, as it reduces product weight and can negatively impact quality [Hautrive et al., 2008]. In our study, the addition of PPP significantly increased (p<0.05) the WHC of the sausages (Table 2). A significant increase was observed at the 4%, 6%, and 8% PPP supplementation levels, with WHC values of 34.5%, 54.7%, and 66.3%, respectively, compared to the control. This increase can be attributed to the high TDF content of the PPP, which forms a gel-like network that effectively traps and holds water within the meat matrix.

As shown in Table 2, the cooking yield of all sausages with PPP was significantly (p<0.05) higher compared to the control (85.96%), and it increased from 87.69% to 89.47% as the amount of PPP in sausages increased from 2% to 8%, respectively. Zaini et al. [2020] discovered that adding 6% banana peel powder to sausages increased the cooking yield to 99.54%, compared to 96.96% determined for the control sausage. Similarly, Mahmoud et al. [2017] discovered that adding 10% orange peel powder increased the cooking yield of burger by up to 57.61% compared to the control sausages (46.53%). The increased water retention capacity can be attributed to the fiber network in meat products, which prevents water loss during cooking. This improvement enhances the texture and sensory properties of the final product.

Color coordinates of chicken sausages

The color of meat and meat products is often used to assess their freshness. Natural plant-based antioxidants can play a vital role in preserving the color of cooked meat products by mitigating lipid oxidation, which can lead to color degradation [Lavado & Cava, 2025].

The color values of chicken sausages are shown in Table 3. The incorporation of PPP significantly (p<0.05) reduced the lightness value (L*) of the sausages compared to the control samples. The darker color of the chicken sausages is likely due to the presence of natural red and yellow pigments, specifically betalains, in PPP [Smeriglio et al., 2021]. The inclusion of PPP significantly (p<0.05) raised the redness (a*) and reduced the yellowness (b*) values of chicken sausages. Increasing the levels of PPP from 2% to 4% resulted in an increase in a* values (from 3.47 to 4.57) and a decrease in b* values (from 12.98 to 11.15) but further increasing the PPP content of sausages had no significant (p≥0.05) effect on these color coordinates. These results are consistent with findings from other studies on the use of PPP in food products. For instance, Parafati et al. [2020] reported that adding PPP as a functional ingredient to bread increased its a* value while decreasing the L* and b* values. Similarly, Bouazizi et al. [2020] found that incorporating PPP powder into biscuits significantly decreased both the L* and b* values.

Table 3

The color coordinates and textural properties of chicken sausages with different levels of prickly pear peel (PPP) powder (2–8% of the total meat batter, w/w).

Textural properties of chicken sausages

The textural characteristics of chicken sausages with PPP are provided in Table 3. The inclusion of PPP in meat batter significantly (p<0.05) increased chewiness and hardness of the chicken sausages, while decreased their cohesiveness. However, no significant (p≥0.05) variation was discovered in springiness. Similar results were reported by Younis et al. [2021] in their study on buffalo meat sausages, where the inclusion of mosambi peel powder increased hardness while decreasing springiness. A variety of factors influence the texture of meat products, including water and lipid content, lean meat particle size, non-meat ingredients, and others [Santhi et al., 2017]. Han & Bertram [2017] noted that the impact of fiber on meat product texture depended on the type of fiber present. They discovered that soluble fiber could increase meat product strength, whereas insoluble fiber triggered the opposite effect. The soluble dietary fiber in PPP can form a three-dimensional gel network. This network can alter the interactions between proteins and water, which in turn influences the tenderness and overall structure of the meat product [Ahmad et al., 2020; Parafati et al., 2020]. Conversely, the insoluble fraction of dietary fiber may lead to a hard and brittle texture by drawing water away from surrounding molecules [Han & Bertram, 2017]. This highlights the importance of considering the type of fiber present in meat products when evaluating its impact on texture and overall quality.

Cohesiveness refers to the internal bond strength within a food product, describing how effectively its components hold together. The findings that higher levels of PPP led to a reduction in cohesiveness are consistent with results of a study conducted by Zaini et al. [2020], where the addition of banana peel powder reduced the cohesiveness of chicken sausages. Moreover, Ktari et al. [2014] reported that removing fiber and adding fat to meat products increased their cohesiveness. When PPP was added, the chewiness value increased compared to the control samples. According to Barretto et al. [2015], chewing fiber-rich food requires more energy. Furthermore, chewiness is influenced by hardness, with chewiness increasing as texture hardness increases.

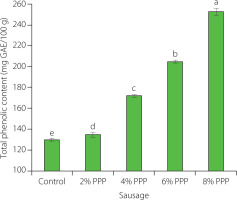

Total phenolic content of chicken sausages

Phenolic compounds have strong antioxidant activity as they can donate hydrogen atoms to interrupt radical chain reactions and convert free radicals into stable molecules, thereby preventing fat rancidity [Santos-Sánchez et al., 2019]. The TPC of the PPP powder used in this study was 734.20±0.63 mg GAE/100 g. The TPC of the chicken sausage samples is displayed in Figure 1. In the chicken sausage samples supplemented with PPP, it ranged from 134.41 to 252.74 mg GAE/100 g, and was significantly higher (p<0.05) than in the control sausage (129.62 mg GAE/100 g). When 8% PPP was added to the meat batter, the TPC of sausages was the highest. This finding aligns with that of Bouazizi et al. [2020], who discovered that the PPP powder used as a biscuit ingredient improved the total phenolic content of the product. The findings indicate a significant relationship between PPP additives and the phenolic content of chicken sausages, with increasing PPP levels leading to an increase in the total phenolic content.

Figure 1

Total phenolic content of chicken sausages with different levels of prickly pear peel (PPP) powder (2–8% of the total meat batter, w/w). Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of three independent measurements. Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences at p<0.05. GAE, gallic acid equivalent.

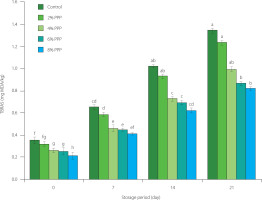

Oxidative stability of chicken sausages

Lipid oxidation results in the production of primary (hydroperoxides) and secondary (carbonyl compounds) products. The latter can be measured using thiobarbituric acid. Unstable hydroperoxides are susceptible to degradation, leading to carbonyl molecules that are capable of interacting with substances like amino acids, peptides, and proteins [Hęś, 2017]. Lipid oxidation negatively affects meat quality and acceptability [Domínguez et al., 2019]. The secondary oxidation products, including MDA, are associated with undesirable meat flavor and odor [Domínguez et al., 2019]. The TBARS values of the chicken sausages containing four different levels of PPP and control samples are shown in Figure 2. During storage, the sausages containing 4%, 6%, and 8% PPP exhibited significantly lower TBARS values (p<0.05) compared to the control sample. At the end of the storage period, the control sample had the TBARS value of 1.344 mg MDA/kg, while the sausage sample with 8% PPP had the value of 0.816 mg MDA/kg. This demonstrates that PPP effectively suppressed lipid oxidation compared to the control by slowing down lipid oxidation throughout the storage period. The antioxidant properties of PPP, attributed to their phenolic content, may be responsible for the decrease in TBARS values. Phenolic compounds possess redox properties that enable them to act as antioxidants by scavenging free radicals, quenching singlet oxygen, and decomposing peroxides [Bai et al., 2025]. Similar findings were reported by Amrane-Abider et al. [2023], who discovered that PPP extract significantly increased the oxidative stability of margarine. Likewise, Gonçalves et al. [2024] found that adding freeze-dried prickly pear pulp, which includes peel components, improved the oxidative stability of chicken patties.

Figure 2

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) values of chicken sausages with different levels of prickly pear peel (PPP) powder (2–8% of the total meat batter, w/w) during storage. Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of three independent measurements. Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences at p<0.05. MDA, malondialdehyde equivalent.

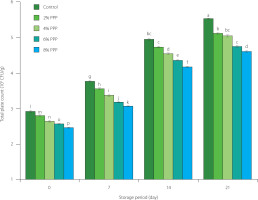

Microbiological stability of chicken sausages

Figure 3 depicts the bacterial load of chicken sausage samples incorporated with PPP. The bacterial load was measured immediately after sausage formulation (0 day), and on days 7, 14, and 21 of cold storage. As expected, the bacterial load values successively increased with storage time. However, the incorporation of PPP significantly delayed bacterial growth compared to the control samples. The PPP-supplemented chicken sausages exhibited lower microbial counts, with values of 2.81×105, 2.65×105, 2.58×105, and 2.47×105 CFU/g for 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8% PPP, respectively. In contrast, the control group had a microbial count of 2.94×105 CFU/g. After 21 days of cold storage, the sausages with 8% PPP had the lowest total microbial count (4.62×105 CFU/g); while the control product had 5.54×105 CFU/g. This can be attributed to the inhibitory effect of PPP’s phenolic compounds on spoilage bacteria. The antimicrobial properties of PPP resulting from the activity of phenolic compounds have been previously reported [Melgar et al., 2017]. Akram et al. [2022] observed a similar decreasing trend in bacterial load values when banana peel powder was added to chicken nuggets. Similarly, Abdel-Naeem et al. [2022] found a similar trend in the microbial load with the addition of fiber-rich peels to meat products.

Figure 3

Total plate count of chicken sausages with different levels of prickly pear peel (PPP) powder (2–8% of the total meat batter, w/w) during storage. Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation of three independent measurements. Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences at p<0.05.

Sensory evaluation of chicken sausages

The sensory scores of the functional chicken sausages containing varying levels of PPP are displayed in Table 4. Various sensory parameters, such as appearance, color, odor, taste, juiciness, hardness, and overall acceptability were assessed using a seven-point hedonic scale. The sensory evaluation indicated that the overall acceptability of the chicken sausages with 2% PPP was rated 4.82, which was not significantly different (p≥0.05) from the control, indicating a similar level of preference among panelists. However, as the incorporation level of PPP increased to 4% and 6%, the overall acceptability scores significantly decreased (p<0.05) to 4.47 and 4.17, respectively. The sausages with 8% PPP had the lowest overall acceptability score of 3.84, which falls within the “slightly dislike” to “neither dislike nor like” range on the seven-point hedonic scale. The increasingly higher content of PPP resulted in increasingly lower scores for appearance, color, odor, taste, and juiciness of the chicken sausages. However, the 2% PPP chicken sausages were rated significantly higher (p<0.05) in terms of hardness compared to the control sausage. Sensory evaluation scores align with findings from a previous study conducted by Chappalwar et al. [2022], which reported similar effects of banana peel powder and flour on the organoleptic properties of chicken patties. In contrast, Zaini et al. [2020] found that incorporating banana peel powder at concentrations exceeding 2% resulted in a decrease in the sensory perception of chicken sausages. Additionally, Parafati et al. [2020] reported that bread made with 10% PPP flour received the highest total sensory evaluation scores, which decreased at PPP flour incorporation levels of 15% and 20%.

Table 4

Sensory scores of chicken sausages with different levels of prickly pear peel (PPP) powder (2–8% of the total meat batter, w/w).

[i] All values are means of triplicate determinations ± standard deviation. Means within the same column with different letters are significantly different at p<0.05. A seven-point hedonic scale was used: 1 (extremely dislike), 2 (dislike), 3 (slightly dislike), 4 (neither dislike nor like), 5 (slightly like), 6 (like), and 7 (extremely like).

CONCLUSIONS

PPP, with its fiber and phenolic compounds, contributes to the health-promoting properties and improved quality of chicken sausages. Supplementation of chicken sausages with 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8% PPP significantly delayed microbial proliferation and suppressed lipid oxidation throughout the storage period, indicating improved product stability. Furthermore, the addition of PPP improved product quality parameters, such as WHC and cooking yield. Sensory evaluations revealed that the control samples and the sausages with 2% PPP achieved comparable overall acceptability scores. Conversely, higher incorporation level of PPP (4–8%) resulted in a significant decline in sensory attributes. In summary, incorporating PPP into chicken sausages offers an effective strategy for enhancing their nutritional value. However, it is crucial to carefully consider the inclusion level to ensure consumer acceptability. The 2% PPP content in meat batter (w/w) represents an optimal balance between enhancing nutritional benefits and preserving desirable sensory qualities of sausages.