ABBREVIATIONS

ABTS, 2,2’-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid); CEL, cellulase; DM, dry matter; DPPH, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; FFA, free fatty acids; GAE, gallic acid equivalent; GSP, grape seed powder; MUFAs, monounsaturated fatty acids; PUFAs, polyunsaturated fatty acids; RI, refractive index; SFAs, saturated fatty acids; SI, saponification index; TE, Trolox equivalent

INTRODUCTION

Grape (Vitis vinifera L.), extensively cultivated worldwide, serves various purposes. According to the International Organisation of Vine and Wine [OIV, 2024], about 57% of global grape production is used for winemaking, 36% for fresh consumption, and roughly 7% for dried grapes. Fresh grapes consist mainly of water (~83%), followed by carbohydrates (~66%), dietary fiber (~14%), proteins (~3%), and minimal lipids (~1%), reflecting their high energy density and nutritional significance [Kalili et al., 2023]. In the wine-making process, 1 kg of crushed grapes yields ~0.2 kg of grape marc [Yang et al., 2021], composed mainly of skins (40%), seeds (30%), and stems (30%), and amounts to more than 9 million tons of agro-industrial waste generated annually on a global scale [Tociu et al., 2021]. The increasing volume of this biomass positions it among the most significant organic residues from the food industry, posing an environmental management challenge but also affording a valuable opportunity for circular bioeconomy initiatives [Palma et al., 2025].

In Peru, the Ica region alone produced approximately 430,000 tons of grapes in 2022, representing almost half (47%) of the national output [Rivera Chávez et al., 2025]. Within this context, the pisco industry, an emblematic segment of Peruvian agro-industry, achieves yields ranging from 1.8 to 30 t/ha and requires between 5.06 and 7.48 kg of grapes to produce 1 L of pisco with 42% (v/v) alcohol content. From 2017 to 2022, the country’s average annual pisco production reached about 6.5 million liters [Palma et al., 2025], which highlights the scale of grape processing and, consequently, the generation of large quantities of by-products such as grape pomace and seeds.

From a sustainability perspective, the valorization of winery waste has become a strategic priority, aligning with global goals for waste minimization and “zero waste” production [Tociu et al., 2021]. Notably, grape seeds represent a high-value fraction of the pomace due to their oil content (8–20%). This lipid fraction is characterized by a high proportion of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), particularly linoleic acid (67–80% of total fatty acids), and monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), especially oleic acid (15%–18% of total fatty acids) [Gitea et al., 2023]. Furthermore, grape seeds are composed of 5–8% of phenolic compounds, and approximately two-thirds of the total phenolic content is distributed within the seed coat, while between 20% and 60% exists in an insoluble form, covalently bound to the structural matrix of the cell wall [Saykova et al., 2018]. Additionally, phenolic compounds, known for their plant-based antioxidant properties, have been linked to the antioxidant and enzyme inhibitory activities of oils, alongside tocopherols and polyunsaturated fatty acids [Özyurt et al., 2021]. Depending on their structure, phenolic compounds can be simple phenols, phenolic acids, flavonoids, xanthones, stilbenes, and lignans [Oluwole et al., 2022].

Oil extraction from oleaginous seeds has increasingly benefited from the use of hydrolytic enzymes, which have proven to be effective in enhancing both yield and process efficiency. Among these, cellulases facilitate the release of oleosomes by weakening the plant cell wall through the breakdown of cellulose microfibrils [Vovk et al., 2023]. The cellulase complex, comprising endoglucanases, exoglucanases, and β-glucosidases, targets β-1,4-glycosidic bonds within cellulose chains to facilitate their breakdown [Łubek-Nguyen et al., 2022]. In this context, although the combined use of enzymes typically results in a more comprehensive disruption of cellular structures, the application of a single enzyme targets only one structural component, such as cellulose, which may lead to incomplete oleosome membrane rupture and require greater mechanical energy input [Vovk et al., 2023]. Some studies have opted for the individual application of enzymes such as cellulase in moringa seed oil extraction [Fernández et al., 2018]. Additionally, enzymes such as cellulase or pepsin have been applied individually in sesame oil extraction due to the incompatibility of their optimal activity conditions. This strategy reflects a technical adaptation aimed at balancing enzymatic efficiency with the operational feasibility of the process [Zaheri Abdehvand et al., 2025].

One approach to improving grapeseed oil extraction includes utilizing protease and/or cellulase enzymes combined with a screw extrusion press. Proteases break down proteins to facilitate oil release, whereas cellulases decompose cellulose in cell walls to boost efficiency [Sun et al., 2022]. An enzymatic combination of pectinase and cellulase in a 3:1 (w/w) ratio was applied to by-products from the Chilean wine industry [Tobar et al., 2005]. In a different approach, pectin lyase, a specific commercial enzyme, was exclusively used for the pretreatment of grape seeds obtained from winemaking residues in Romania [Tociu et al., 2021]. In view of the above, this study aimed to evaluate the quality and antioxidant capacity of grapeseed oils obtained through hydraulic pressing with cellulase pretreatments, using different enzyme-to-substrate ratios and enzymatic treatment times. The oil properties were compared to those of grape seed oil pressed without enzyme support to show the effect of cellulase pretreatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

The grape seeds (red and white Borgoña varieties, Vitis labrusca × V. vinifera), obtained as by-products from the winemaking process at Zapata Winery (Lunahuaná District, Cañete Province, Lima, Peru), were kindly provided in the framework of the research project “Use of residues of fruit processing: grapes (V. vinifera) and passion fruit (Passiflora edulis)” by the Universidad Nacional Agraria “La Molina” (Lima, Peru).

Extraction of grapeseed oil with and without enzymatic pretreatment

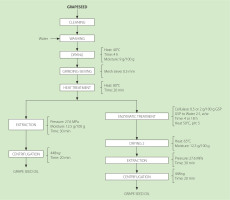

The procedure for obtaining grapeseed oil with and without enzymatic pretreatment is illustrated in Figure 1. The seeds were cleaned, washed, and dried to a moisture content of 9 g/100 g at 40°C using a tray dryer (local manufacture, Lima, Peru). The dried seeds were ground in a hand mill (Corona, Manizales, Colombia), and the resulting powder was sieved through a 35-mesh (0.5 mm) stainless steel sieve. Before oil extraction, the grapeseed powder was heated at 80°C for 20 min to inactivate endogenous enzymes, coagulate proteins, and promote oil droplet coalescence [Santoso et al., 2014]. Oil extraction was performed on 350 g of powder with a moisture content of 12.5 g/100 g using a manual hydraulic press (maximum capacity 48 MPa; local manufacture, Peru), applying a pressure of 27.6 MPa for 30 min at room temperature. The extracted oil was centrifuged at 448×g for 20 min using a centrifuge (Hettich EBA 206, Tuttlingen, Germany) to remove residual solids.

Figure 1

Process flow for obtaining grapeseed oil with and without cellulase treatment. GSP, grape seed powder.

The grape seed powder (GSP) previously conditioned at 80°C for 20 min was used for enzymatic pretreatment. The thermally-treated powder was dispersed in distilled water (2:1, w/w) by vortexing and treated with cellulase (CEL) from Aspergillus niger (Sigma-Aldrich, Waltham, MA, USA; cellulase activity ≥0.3). The enzymatic hydrolysis was conducted in a climatic chamber (Memmert, Schwabach, Germany) at 50°C and pH 5. Two enzyme-to-substrate ratios (0.5 or 2 g CEL/100 g grape seed powder, GSP) and two incubation times (4 or 18 h) were evaluated resulting in four treatments: T1 (0.5 g CEL/100 g GSP, 4 h), T2 (0.5 g CEL/100 g GSP, 18 h), T3 (2 g CEL/100 g GSP, 4 h), and T4 (2 g CEL/100 g GSP, 18 h). After incubation treatment, the enzymatically-treated GSP was dried at 65°C to a moisture content of 12.5 g/100 g using a laboratory oven (Model 4-1411, Instru, Lima, Peru). This drying stage ensured the inactivation of residual enzymatic activity and stabilized the substrate for subsequent hydraulic press oil extraction.

Oil yield was calculated as the ratio between the mass of oil extracted (MOI) and the initial dry matter (DM) of seeds (DMS) using Equation (1), while extraction efficiency was determined relative to the total oil content (TOC) obtained by ether extraction using Equation (2):

Physical and chemical analyses

The oils obtained from the control (T0) and the four enzymatic pretreatments (T1–T4) were analyzed for moisture content (g/100 g oil) [AOAC, 2007; method 926.12], free fatty acid content (FFA, g oleic acid/100 g oil) [AOAC, 2007; method 940.28], and peroxide value (PV, meq O2/kg oil) [AOAC, 2007; method 965.33]. The acidity index (AI) was derived from the free fatty acid measurement using the conversion AI=1.99 × FFA and expressed in mg KOH/g oil. Additionally, iodine index (g I2/100 g oil), refractive index (RI, dimensionless), density (g/mL), saponification index (SI, mg KOH/g oil), unsaponifiable matter (g/kg oil), and p-anisidine value (dimensionless) were determined according to AOAC methods 920.159, 921.08, 920.212 [2007], 920.160 [1990], 933.08 [1998], and AOCS Cd 18-90 [1990], respectively.

The total phenolic content (TPC) was determined using the Singleton et al. [1999] colorimetric method with a Folin–Ciocalteu reagent with slight modifications according to Günç Ergönül & Aksoylu Özbek [2018]. Approximately 15 g of oil was dissolved in 20 mL of n-hexane and extracted three times with a MeOH/H2O (40:60, v/v) mixture to a final extract volume of 50 mL. Then, 1 mL of the extract was mixed with 5 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 20 mL of Na2CO3 solution (20%), and the volume was adjusted to 100 mL with distilled water. After 30 min of incubation in the dark at room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 725 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA). The results were expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per kg of oil (mg GAE/kg oil).

The antioxidant capacity of the oils was evaluated using the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2’-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assays, according to the original methods described by Brand-Williams et al. [1995] and Re et al. [1999], respectively, with modifications based on Samaniego Sánchez et al. [2007]. The methanolic extract obtained from the oil sample was used for the DPPH assay. Two grams of the oil were mixed with 1 mL of n-hexane and 2 mL of anhydrous methanol. The mixture was vortexed for 2 min and centrifuged at 700×g for 5 min to separate the lipid and methanolic phases. The methanolic phase was re-extracted once under the same conditions, and this extract was used for analysis. For the assay, 400 μL of the methanolic extract was mixed with 3 mL of a 0.1 mM DPPH• solution. The mixture was shaken and kept in the dark at room temperature for 60 min until equilibrium was reached, and the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. For the ABTS assay, 100 μL of the oil sample (diluted 1:4, v/v, in n-hexane) was mixed with 2 mL of the ABTS•+ solution. The ABTS radical cation was generated from a 7 mM ABTS stock solution reacted with 140 mM potassium persulfate, and the mixture was allowed to stand in the dark for 12 h before use. After 30 min of reaction, the absorbance was measured at 734 nm. Results from both assays were expressed as mmol Trolox equivalents per kg of grape seed oil (mmol TE/kg oil).

Two oil samples were analyzed for their fatty acid composition following the method of Prévot & Mordret [1976], with minor modifications. One sample was the untreated control (T0), and the other was obtained under the selected enzyme pretreatment and reaction time (T2). Approximately 50 mg of the oil were converted to fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) and analyzed using a Perkin Elmer Autosystem XL gas chromatograph with a flame ionization detector (FID) (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a Supelco SP-2560 capillary column (100 m × 0.25 mm, 0.20 μm; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The injector and detector temperatures were 250°C and 270°C, respectively, with helium as the carrier gas (1.0 mL/min) and an injection volume of 2 μL. Fatty acids were identified using a certified FAME standard mix (Supelco, 37 components), and results were expressed as relative percentages of total fatty acids.

Statistical analysis

The analysis results were presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD), with each analysis performed in triplicate. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to identify statistically significant differences (p<0.05) between treatments, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test for post hoc analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using Statgraphics Centurion version 16 (Stat Point Technologies, Inc., VA, USA). In addition, Pearson’s correlation analysis and principal component analysis (PCA) were conducted using RStudio software (v. 2023.09.1, Boston, MA, USA) with the FactoMineR, factoextra, and corrplot packages to evaluate associations among the studied parameters and visualize sample groupings.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Extraction of grapeseed oil

The total fat content of grape seeds, determined by ether extraction, was 10.4 g/100 g DM. The results of grapeseed oil extraction without (T0) and with enzymatic pretreatment (T1–T4) are shown in Table 1. The enzymatic pretreatment improved the oil yield and extraction efficiency compared to the traditional approach. Treatments T2, T3, and T4 were particularly effective, yielding 9.89, 9.83, and 9.59 g/100 g DM and achieving extraction efficiencies of 95.05%, 94.42%, and 92.11% (w/w), respectively. According to Carmona-Jiménez et al. [2022], oil yields from grape pomace were 3.81 to 6.71 g /100 g for white varieties and 8.89 to 9.73 g/100 g for red ones. For seeds, the cited authors obtained oil yields varying between 14.74 and 22.52 g/100 g for white and 12.46 and 15.89 g/100 g for red varieties, and these values were higher than those determined in our study for grape seeds of cv. Vitis labrusca × V. vinifera. Nevertheless, the positive effect of cellulase pretreatment was consistent with literature data; Tobar et al. [2005] obtained a 55% (w/w) extraction efficiency from grape seeds after using a 2% (w/w) solution of Ultrazym-Celluclast enzymes (enzyme-to-substrate ratio of 3:1) for 9 h, compared to a 30% (w/w) extraction rate of the enzyme-less control.

Table 1

Oil yield, extraction rate, and physicochemical characteristics of oils obtained from untreated (T0) and cellulase-treated (T1–T4) grape seed powder (GSP) of cv. Vitis labrusca × Vitis vinifera.

[i] Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n=3). Different letters indicate significant differences (p<0.05) among samples within the row. DM, dry matter; T0, control (without enzymatic pretreatment); T1, 0.5 g cellulase (CEL)/100 g GSP for 4 h; T2, 0.5 g CEL/100 g GSP for 18 h; T3, 2 g CEL/100 g GSP for 4 h; T4, 2 g CEL/100 g GSP for 18 h.

Researchers also noticed an increase in the oil extraction rate from other seeds after enzymatic treatments. For example, Anwar et al. [2013] reported values for flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) ranging from 35% to 38% (w/w) compared to 33% (w/w) of the control. Fernández et al. [2018] achieved a 28.4% (w/w) yield in moringa oil extraction through an enzymatic treatment, which involved 24 h hydrolysis using 2% (w/w) hemicellulase, surpassing the 25% (w/w) yield obtained in the control group. In contrast, Candan & Arslan [2021], who investigated the effects of an enzyme preparation with cellulolytic, peptinolytic, and hemicellulolytic activity on grapeseed oil extraction, found that the use of 1 g of enzyme per 100 g of seeds did not increase the oil yield significantly. Consistent with these findings, Tociu et al. [2021] reported that comparable oil extraction yields could be obtained when using a single enzyme, instead of multi-enzyme cocktails, and that this strategy could substantially reduce processing costs while maintaining similar extraction performance.

Physicochemical characteristics

The physicochemical characteristics of treatments T0–T4 are presented in Table 1. The enzyme-treated oils had a higher FFA content (1.26–1.59 g /100 g oil) than the enzyme-less control (1.05 g /100 g oil). According to the Codex Alimentarius Commission’s CXS210-1999 Standard for Named Vegetable Oils [Codex Alimentarius, 1999], the acceptable upper limits of FFA are 0.3% oleic acid for refined oils and up to 2% for most cold-pressed and virgin oils, indicating that the values obtained in this study remain within the acceptable quality range. Moreover, oils containing less than 5% FFA are generally classified as edible, since excessive free fatty acids accelerate oxidative degradation and rancidity during storage [Lamani et al., 2021]. A similar increase in FFA content following enzymatic pretreatment has been reported for flaxseed, apricot, and grapeseed oils, where the moisture introduced with the enzyme carrier solution promoted triglyceride hydrolysis [Candan & Arslan, 2021]. Furthermore, the activation of endogenous lipases during seed grinding was suggested to contribute to FFA formation [Candan & Arslan, 2021].

The grapeseed oils exhibited acidity indices ranging from 2.20 to 2.89 mg KOH/g oil, being slightly higher in the enzymatically-treated samples (T1–T4) than in the untreated control (T0) (Table 1). However, all values remained below the maximum limit (4.0 mg KOH/g oil) established by the Codex Alimentarius standard CXS 210-1999 [Codex Alimentarius, 1999]. These results were slightly higher than those reported by de Menezes et al. [2023] for grape seed oils from the Ives and Cabernet Sauvignon varieties extracted by hydraulic press or Soxhlet, which ranged from 1.87 to 2.09 mg KOH/g oil.

The peroxide value of the oils ranged from 7.24 mEq O2/kg in T0 to 11.96 mEq O2/kg in T1, with intermediate values observed in T2–T4 (9.93–11.24 mEq O2/kg) (Table 1). This increase suggests a moderate intensification of oxidative reactions following enzymatic pretreatment, possibly linked to the release of prooxidant phenolics or trace metal ions during cell wall disruption [de Menezes et al., 2023]. Comparable behavior was observed by Candan & Arslan [2021], who reported that increased moisture during enzymatic treatments facilitated primary oxidation reactions and resulted in higher peroxide values, particularly in grape seed and sesame oils. Notably, the peroxide value of T2 (9.93 mEq O2/kg) was comparable to that reported by de Menezes et al. [2023] for the Ives variety (9.98 mEq O2/kg), indicating similar oxidative behavior in hydraulically pressed oils. Despite this increase, all values remained below the Codex Alimentarius [1999] limit for virgin oils (15 mEq O2/kg), confirming that enzymatic pretreatment did not compromise oxidative stability. The slight rise in peroxide levels, which reflects the accumulation of primary oxidation products, could be associated with triglyceride hydrolysis induced by cellulase, releasing free fatty acids that accelerate lipid peroxidation, particularly in oils rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, which are inherently more susceptible to oxidative degradation [Ravagli et al., 2025].

The moisture content of the oils remained consistently low (0.47–0.48 g/100 g oil) (Table 1), a desirable characteristic that limits hydrolytic reactions and minimizes oxidative susceptibility during storage. Similar findings were reported by de Menezes et al. [2023], who obtained oils with <1% moisture after drying grape seeds at 40°C using pressing, Soxhlet, and ultrasound extraction methods. According to the International Olive Council [IOC, 2019], the recommended moisture content should be below 0.20% for virgin olive oil and 1.50% for crude pomace oil, confirming that the values observed in this study fall within acceptable quality limits.

In a subsequent stage, only T0 and T2 were analyzed for complementary quality parameters, including iodine value, saponification index (SI), unsaponifiable matter, p-anisidine value, refractive index (RI), and density. The iodine value measures the degree of unsaturation in oils and fats, providing an indirect indicator of oxidative susceptibility, with higher values indicating greater unsaturation [Hagos et al., 2023]. In this study, T0 and T2 showed iodine values of 133.6 and 131.7 I2/100 g oil (Table 1), respectively, both within the range established by the Codex Alimentarius [1999] for grapeseed oil (128–150 I2/100 g).

The saponification index (SI) provides important information about the molecular characteristics of oils. When the SI of an oil is below 190 mg KOH/g, it indicates the presence of high-molecular-weight triglycerides, which are typically esterified with polyunsaturated fatty acids such as linoleic and linolenic acids [Lamani et al., 2021]. The SIs for T0 and T2 were slightly below the Codex range for grape seed oil (188–194 mg KOH/g oil), whereas the unsaponifiable fraction remained below 20 g/kg, in agreement with the standard [Codex Alimentarius, 1999]. These findings align with those reported by de Menezes et al. [2023] for grapeseed oils and by Fernández et al. [2018] for moringa oils obtained with hemicellulase pretreatment.

The p-anisidine value is a reliable indicator of secondary oxidation in vegetable oils, as it quantifies non-volatile aldehydes resulting from the decomposition of primary oxidation products. Specifically, it measures reactive aldehydic compounds, such as 2-alkenals and 2,4-dienals, which are produced during the advanced stages of lipid oxidation. Elevated p-anisidine values indicate pronounced oxidative degradation and a consequent decline in oil quality. For edible oils, values should remain below 10, whereas those under 2 are considered indicative of high-quality oils [Gharby et al., 2025]. In this study, the p-anisidine values were 1.83 for T0 and 1.71 for T2, showing no significant differences (p≥0.05). This behavior agrees with findings reported by Candan & Arslan [2021], who observed that enzymatic treatment did not significantly affect p-anisidine values in grape seeds and flaxseed oils, despite variations in primary oxidation indices. Fernández et al. [2018] reported comparable results for oils from enzymatically-treated moringa seeds, supporting the observation that this process does not substantially influence this oxidation index.

The refractive index of T0 and T2 was 1.48 at 25°C, slightly higher but consistent with the mean RI of conventional edible oils such as corn, soybean, olive, and sunflower (~1.47) [Gunstone, 2008]. Regarding density, the oils with and without enzymatic pretreatment (T1–T4) exhibited values within the range established for seed oils (0.920–0.926 g/mL at 20°C) according to the Codex Alimentarius [1999]. These results indicate that the enzymatic treatment did not adversely affect the physicochemical integrity or overall quality of the oils.

Phenolic content and antioxidant capacity

Phenolic compounds, owing to their hydrophilic nature, exhibit low solubility in the oil phase, and only a small fraction is transferred from the solid matrix during oil extraction [Saykova et al., 2018]. Consequently, most phenolics remain in the seed cake after pressing [Vidal et al., 2022]. Therefore, processing strategies that promote cell wall disruption and facilitate the migration of phenolic compounds into the oil phase, such as enzyme-assisted pretreatments, can substantially enhance their recovery [Brienza et al., 2025]. Enzymatic treatments applied during oil extraction enable the hydrolysis of cell wall polysaccharides, releasing bound phenolics and enhancing the bioactive profile of the resulting oil [Zaheri Abdehvand et al., 2025].

Grapeseed oils pretreated with cellulase exhibited significantly higher total phenolic content (TPC), showing an increase of 14% to 119% compared to the control (Table 2). The TPC of the oils ranged from 127.5 to 279.2 mg GAE/kg, values comparable to those reported by Rombaut et al. [2015] for grape seeds from Distillerie Jean Goyard in France (48–153 mg GAE/kg) and by Konuskan et al. [2019] for several varieties, including Sauvignon Blanc (102.55 mg GAE/kg), Syrah (148.21 mg GAE/kg), Merlot (151.51 mg GAE/kg), Sangiovese (177.31 mg GAE/kg), and Cabernet Sauvignon (182.41 mg GAE/kg). Kapcsándi et al. [2021] reported values around 240 mg GAE/kg for Pinot Noir, whereas Mollica et al. [2021] documented markedly higher TPC (12,030 mg GAE/kg) in Montepulciano grape seeds. These variations can be attributed to intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including grape cultivar, environmental conditions, agronomic practices, and extraction parameters, as extensively discussed by Vidal et al. [2022], who emphasized the influence of post-harvest conditions and enzymatic pretreatment on phenolic transfer efficiency.

Table 2

Total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity in ABTS and DPPH assays of oils obtained from untreated (T0) and cellulase-treated (T1–T4) grape seed powder (GSP) of cv. Vitis labrusca × Vitis vinifera.

[i] Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n=3). Different letters indicate significant differences (p<0.05) among samples within the column. GAE, gallic acid equivalent; TE, Trolox equivalent; T0, control (without enzymatic pretreatment); T1, 0.5 g cellulase (CEL)/100 g GSP, 4 h; T2, 0.5 g CEL/100 g GSP, 18 h; T3, 2 g CEL/100 g GSP, 4 h; T4, 2 g CEL/100 g GSP, 18 h.

Comparable patterns have been reported in other oilseeds subjected to enzymatic treatments. Teixeira et al. [2013] found significantly higher extraction rates of phenolic compounds (51%) and carotenes (153%) using tannase and cellulase plus pectinase, respectively, in palm oil. Similarly, Anwar et al. [2013] reported that oil pressed from flaxseeds treated with Viscozyme L, Kemzyme, and Feedzyme (2% w/w; 6 h; 40°C; 50% moisture) contained more total phenolics (8.61–10.5 mg GAE/100 g) than the oil from the control seeds (6.21 mg GAE/100 g). Özyurt et al. [2021] found that enzymatic extraction with Alcalase 2.4 L increased the TPC (3.30 mg GAE/kg) compared to cold pressing (2.97 mg GAE/kg) in oil of tomato seeds, although with a lower oil yield (9.66% vs. 12.80%, w/w), emphasizing the enzyme’s role in enhancing bioactive compound release.

The TPC values obtained in this study were also higher than those achieved through other extraction methods applied to grapeseed oil. Ubaid & Saini [2024] evaluated several extraction techniques and reported 117.54 mg GAE/kg (cold-pressed), 109.77 mg GAE/kg (hexane extraction), 127.18 mg GAE/kg (supercritical CO2 extraction), 132.01 mg GAE/kg (supercritical CO2 + 10% ethanol extraction), and 123.53 mg GAE/kg (p-cymene-assisted extraction). The higher values obtained in the present study indicate that cellulase pretreatment, conducted under mild and solvent-free conditions, represents an effective green strategy for enhancing phenolic recovery in vegetable oils.

The effectiveness of enzyme-assisted pretreatments largely depends on operational parameters such as enzyme concentration, incubation time, temperature, and pH, which determine the extent of cell wall hydrolysis and the subsequent release of phenolics [Tociu et al., 2021]. The results of this study revealed that the interaction between cellulase-to-substrate ratio and hydrolysis duration was decisive. Treatment T2 (0.5 g CEL/100 g GSP; 18 h; 50°C; pH 5) yielded the highest TPC (279.2 mg GAE/kg oil), indicating that a moderate enzyme-to-substrate ratio and a controlled hydrolysis period favor efficient cell wall disintegration and gradual phenolic diffusion. Conversely, increasing the enzyme load to 2 g CEL/100 g GSP (T3–T4) did not yield further improvement, possibly due to enzyme saturation or diffusional limitations within the solid matrix. Numerous studies have corroborated the influence of enzyme concentration and incubation time on extraction efficiency. In grape seeds, Sun et al. [2022] demonstrated that enzyme-to-substrate ratio was the most significant factor, while hydrolysis time (2–4 h) had no notable effect within that range. Conversely, Zaheri Abdehvand et al. [2025] found that the application of cellulase (3%, w/v, pH 7) or pepsin (2%, w/v, pH 2) for 6 h at 40°C in sesame seeds significantly enhanced both TPC and antioxidant capacity, nonetheless, cellulase (oil yield: 25.85%) exhibited superior efficiency in extracting oil, pigments, and proteins, whereas pepsin (oil yield: 21.83%) was more effective in promoting carbohydrate release and modestly enhancing antioxidant capacity. Both enzymatic methods demonstrated sustainability and efficiency, positioning them as promising alternatives to conventional solvent-based extraction techniques. Liu et al. [2016] reported that hydrolysis periods up to 18 h under mild conditions improved wall disintegration and phenolic diffusion, while Tociu et al. [2021] identified an optimal duration of 24 h using pectin lyase in grape seeds.

Overall, the results demonstrate that cellulase pretreatment for 18 h enables effective hydrolytic action on the grape seed matrix, facilitating the migration of phenolics into the oil phase under environmentally sustainable conditions. Considering that phenolic compounds contribute significantly to the antioxidant potential of vegetable oils, their antioxidant capacity was subsequently evaluated.

The antioxidant capacity of the five grape seed oils is presented in Table 2. Oils from enzymatically-treated seed powders demonstrated significantly higher antioxidant capacities than the control in both assays. T2 reached the highest values, with 1.81 mmol TE/kg (ABTS assay) and 0.128 mmol TE/kg (DPPH assay). It should be noted that antiradical activity against ABTS•+ was evaluated directly in the oil (lipophilic matrix), whereas DPPH• scavenging activity was assessed after extraction with a polar solvent; consequently, the ABTS assay response likely reflects the contribution of lipophilic antioxidants (e.g., tocopherols and carotenoids), explaining the higher apparent capacity in this assay compared with DPPH, in line with prior observations in oil systems [Anwar et al., 2013].

Comparable findings have been reported in other vegetable oils. Zaheri Abdehvand et al. [2025] observed a significant increase in antioxidant capacity of sesame oils obtained by cellulase and pepsin-assisted extraction relative to the control; notably, the cellulase-treated oil showed the highest DPPH radical inhibition (~95%), followed by pepsin (~93%), while the control reached ~85%, underscoring the positive effect of enzyme-assisted extraction on antioxidant performance. This enhancement has been attributed to the enzymatic release of bioactive constituents, including phenolics, tocopherols, carotenoids, and chlorophylls, which collectively contribute to greater oxidative stability [Latif et al., 2008]. Additionally, the enzymatic hydrolysis of phenolic compounds and the reduction of polyphenol–polysaccharide complexation further enhance the antioxidant potential of the extracted oil [Latif et al., 2008; Teixeira et al., 2013].

Evidence from previous studies indicates that enzyme type, its concentration, and incubation time significantly affected not only the oil extraction yield, but also phenolic recovery and antioxidant capacity of the oils [Anwar et al., 2013]. The three enzymes (Viscozyme L, Feedzyme, and Kemzyme) employed for the enzymatic pretreatment of flaxseed oil extraction yielded different extraction rates (38%, 35.2%, and 36.5%, respectively). However, despite the relatively high oil yields, the use of Kemzyme resulted in the lowest total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity, suggesting that higher extraction efficiency does not necessarily correspond to improved bioactive potential [Anwar et al., 2013]. Moreover, enzymatic pretreatment with pectinases, proteases, and cellulases significantly improved the TPC in pomegranate seed oil, thereby enhancing its antioxidant capacity [Kaseke et al., 2021]. The results demonstrate that the enzymatic treatment enhances the release of antioxidant compounds, leading to improved antioxidant potential and probably oxidative stability of grapeseed oil.

Fatty acid composition

The fatty acid composition of the grapeseed oil extracted without and with cellulase pretreatment at 0.5 g CEL/100 g GSP for 18 h (T2) revealed a consistent profile (Table 3). Both oils were rich in PUFAs (>70% of total fatty acids), whereas saturated fatty acids (SFAs) accounted for <12% of total fatty acids. The major fatty acids identified, in a descending order of content, were linoleic, oleic, palmitic, stearic, and linolenic acids. Linoleic acid was the predominant fatty acid, accounting for 69.8% (T0) and 69.8% (T2) of total fatty acids, confirming the high PUFA character typically attributed to grapeseed oil. Notably, the stearic acid content increased from 4.25% in the untreated oil (T0) to 4.63% in T2. This result aligned with findings of Gitea et al. [2023], who reported that stearic acid levels in grapeseed oil obtained by different methods ranged from 2.75% to 5.32% of total fatty acids. Similarly, Kapcsándi et al. [2021] determined a notable content of stearic acid in grape seed oils, ranging from 3.42% to 9.93% of total fatty acids, further confirming the variability depending on plant cultivar. Candan & Arslan [2021] also observed a slight increase in stearic acid content (from 4.32% to 4.33%) when applying a cellulolytic–pectinolytic enzyme complex and attributed this behavior to moisture-mediated hydrolysis and native lipase activity rather than to enzymatic modification of fatty acid biosynthesis. This interpretation is consistent with findings from a study by Zaheri Abdehvand et al. [2025], who confirmed that cellulase primarily enhanced oil release by disrupting cell wall polysaccharides without altering triglyceride structure or fatty acid composition.

Table 3

Fatty acid composition (% total fatty acids) of oils obtained from untreated (T0) and cellulase (CEL)-treated grape seed powder (GSP) (T2, 0.5 g CEL/100 g GSP, 18 h) of cv. Vitis labrusca × Vitis vinifera.

The fatty acid profile of the grape seed oil was consistent with compositions reported for grapeseed oils extracted using different methods and cultivars. Carmona-Jiménez et al. [2022] reported grapeseed oil compositions from five grape varieties containing linoleic acid (66.0%–69.0% of total fatty acids), oleic acid (17.0%–20.0% of total fatty acids), palmitic acid (8.20%–9.40% of total fatty acids), and stearic acid (3.70%–5.20% of total fatty acids). Odabaşioğlu [2023] analyzed grape seed oils from 16 grape genotypes obtained by Soxhlet extraction, identifying 13 to 15 fatty acids. The linoleic acid content ranged from 56.13% to 69.36% of total fatty acids, and the oleic acid content ranged from 15.99% to 30.97% of total fatty acids. Similarly, Di Stefano et al. [2021] reported linoleic acid levels of 67.2–71.1% and stearic acid levels of 3.26–4.33% in cold-pressed grapeseed oils. Likewise, de Menezes et al. [2023] observed linoleic acid contents of 65.25–68.76% of total fatty acids in oils obtained via pressing, Soxhlet, and ultrasounds. Taken together, these results confirm that the oils obtained in this study fall within the compositional variability expected for grape seed oil and meet the ranges established by the Codex Alimentarius [1999] (C16:0: 5.5–11.0%; C18:0: 3.0–6.5%; C18:1: 12.0–28%; C18:2: 58.0–78%; C18:3: <1%).

Finally, the preservation of high PUFA levels (70.3% in both T0 and T2) alongside stable U/S ratios (unsaturated/saturated fatty acids) supports the observation of Candan & Arslan [2021] that enzyme pretreatment may increase oil recovery efficiency without compromising lipid nutritional quality. In this case, the use of a single cellulase enzyme allowed achieving results comparable to those obtained with multi-enzyme complexes, indicating that more complex enzymatic systems are not necessary to maintain or enhance the fatty acid composition of grapeseed oil.

Relationship between oil characteristics

Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed strong associations among oil extraction yield, oil quality parameters, total phenolic content, and antioxidant capacity (Table 4). Yield exhibited very strong positive correlations with antioxidant capacity in DPPH and ABTS assays (r=0.908 and r=0.852, respectively) and a strong correlation with TPC (r=0.756) and peroxide value (r=0.752). These results indicate that greater extraction efficiency was accompanied by higher recovery of phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity, likely due to the enhanced release of bound phenolics and bioactive molecules facilitated by enzymatic cell wall degradation [Kaseke et al., 2021]. Results of DPPH and ABTS assays showed a very strong positive correlation (r=0.937, p<0.001), confirming that both assays provide consistent assessments of antioxidant capacity in grapeseed oil. Total phenolic content also exhibited strong positive correlations with ABTS and DPPH assay results (r=0.877, p<0.01), underscoring the predominant contribution of phenolic compounds to the antioxidant behavior of the samples. These relationships align with the well-established link between phenolic content and radical scavenging activity, where hydroxyl-rich phenolics efficiently donate hydrogen atoms or electrons to neutralize free radicals [Vucane et al., 2024].

Table 4

Coefficients of linear correlations among oil yield, physicochemical parameters, total phenolic content, and antioxidant capacity (in ABTS and DPPH assays) of grape seed oils obtained from cv. Vitis labrusca × Vitis vinifera seed powders without and with enzymatic pretreatment in different conditions.

Among oil quality parameters, free fatty acids showed a very strong positive correlation with the peroxide value (r=0.933, p<0.001) and a strong correlation with the acidity index (r=0.753, p<0.01), while acidity index also significantly correlated with the peroxide value (r=0.794, p<0.01) (Table 4). These relationships confirm the close association among oxidative stability indicators, as hydrolysis and oxidation processes tend to progress simultaneously, leading to increased levels of free fatty acids and primary oxidation products [Kaseke et al., 2021; Symoniuk et al., 2022].

In contrast, the correlations of TPC and antioxidant capacity with oil quality parameters were weak, indicating that phenolic content and oxidative indicators evolve independently under the studied conditions. This trend suggests that, although phenolic compounds contribute to the oil’s antioxidant defense, their content is not the main determinant of immediate oxidation status. Similar observations were reported by Symoniuk et al. [2022] and Kaseke et al. [2021], who found that the relationship between phenolic compounds and primary oxidation indices in vegetable oils may be limited due to differences in compound polarity, solubility, and reaction kinetics within the lipid matrix.

Principal component analysis

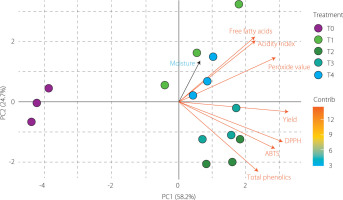

PCA was conducted using yield, moisture content, free fatty acid content, acidity index, peroxide value, total phenolic content, and results of ABTS and DPPH assays across treatments (T0–T4). The first two principal components explained 82.9% of the total variance (PC1: 58.2%, PC2: 24.7%), effectively summarizing most of the data variability. As shown in the biplot (Figure 2), yield, total phenolic content, and ABTS and DPPH results exhibited high loadings on PC1, forming a cluster associated with extraction efficiency and antioxidant capacity. In contrast, free fatty acids, acidity index, and peroxide value grouped in the opposite direction, reflecting indicators related to oil degradation. Moisture content, which contributed primarily to PC2, remained isolated from these clusters, indicating a secondary and independent effect on the dataset. These results highlight that PC1 differentiated treatments by functional enrichment, while PC2 captured compositional differences, consistent with previous studies on enzyme-assisted extraction of plant oils [Kaseke et al., 2021].

Figure 2

Biplot of principal component analysis (PCA) of grapeseed oils (Vitis labrusca × Vitis vinifera) obtained by hydraulic pressing without (T0) and with cellulase pretreatments (T1–T4), showing relationships among oil yield, physicochemical parameters, total phenolic content, and antioxidant capacity in ABTS and DPPH assays. The biplot illustrates both the loading patterns of the variables and the distribution of treatments along PC1 and PC2.

The distribution of treatments further reflected these relationships. Treatments T2 and T3 were positioned close to the vectors representing oil yield, total phenolic content, and antioxidant capacity (DPPH/ABTS), indicating that cellulase-assisted pretreatment enhanced both extraction efficiency and the release of bioactive phenolic compounds. In contrast, T0, which did not receive enzymatic treatment, appeared on the negative side of PC1, reflecting lower extraction efficiency and minimal release of functional compounds.

Along PC2, T1 projected toward the positive axis, associated with an increased free fatty acid content and acidity index. Meanwhile, T1 and T4 were located closer to the moisture vector, suggesting milder enzymatic effects and a less pronounced improvement in functional parameters compared to T2 and T3. Although the enzymatically-treated oils (T1–T4) showed slightly higher acidity and peroxide values than the control, all samples remained within the quality limits established by the Codex Alimentarius [1999], confirming compliance with international standards. Overall, the biplot indicates that treatments promoting greater phenolic release (particularly T2 and T3) were associated with higher extraction efficiency and antioxidant capacity, whereas treatments with milder enzymatic effects (T1 and T4) showed more moderate responses.

The PCA configuration, in agreement with the correlation analysis, revealed an inverse association between oil oxidation indicators (free fatty acid content, acidity index, peroxide value) and functional parameters (TPC and antioxidant capacity). This finding suggests that the higher content of phenolics may have mitigated oxidative degradation during enzymatic extraction by stabilizing unsaturated lipids and interrupting radical chain reactions. Similar trends have been reported by Vardakas et al. [2024], who observed that cellulase pretreatment enhanced the release of bound phenolic compounds, thus improving antioxidant performance and oxidative resilience. Moreover, Kaseke et al. [2021] highlighted that enzyme-assisted systems strengthened the interdependence between phenolic enrichment and oxidative stability, confirming the protective role of phenolics in maintaining oil quality.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated that the enzymatic pretreatment of grape seeds with cellulase enhanced both oil extraction efficiency and the enrichment of phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity, while maintaining physicochemical properties within acceptable quality standards.

Correlation and principal component analyses confirmed a strong positive relationship between extraction yield and bioactive compound content, suggesting that enzymatic activity promoted the release of functional metabolites during pressing. Among the evaluated treatments, T2 showed a distinctive performance, combining higher extraction efficiency with greater functional enrichment.

Overall, cellulase pretreatment improved both the extraction efficiency and functional properties of grapeseed oil. The conditions of enzymatic pretreatment significantly determined the TPC and antioxidant capacity of the oil; a lower enzyme concentration for a longer time of action (T2) proved to be the best combination among the treatments used. In conclusion, enzymatic pretreatment represents a viable and sustainable technological strategy for the valorization of grape seed by-products, supporting the development of functional vegetable oils and contributing to a more circular use of agro-industrial residues.