INTRODUCTION

Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.) is a tropical fruit tree that has been widely cultivated in Southeast Asia, Oceania, South America and Africa [Jahurul et al., 2020a]. Rambutan seeds are a by-product of rambutan fruit processing industry such as dried rambutan, rambutan in sugar syrup, jam, jelly, and rambutan juice [Afzaal et al., 2023]. Rambutan seeds account for about 4-7% of the rambutan fruit weight [Jahurul et al., 2020a]. This by-product contains various nutrients valuable for humans. The lipid content of rambutan seeds is roughly 33.4 g/100 g dry matter (dm) [Hernández-Hernández et al., 2019], in which

the unsaturated fatty acid level is approximately 48.1% of total lipids [Chimplee & Klinkesorn, 2015]. According to Jahurul et al. [2020b], the melting point of rambutan seed lipid is similar to that of cocoa butter; as a result, it can be used to partially replace cocoa butter in chocolate processing. The protein content of rambutan seeds is about 7.8 g/100 g dm [Hernández-Hernández et al., 2019]; specifically, the albumin fraction of rambutan seed proteins is reported to have good functional properties including high gelation, emulsifying and foaming capacities [Vuong et al., 2016]. The total carbohydrate content of rambutan seeds is approximately 46 g/100 g dm; the main components are starch and dietary fiber [Hernández-Hernández et al., 2019]. Rambutan seeds also contain minerals like calcium, zinc, iron and manganese [Akhtar et al., 2017] and vitamins such as thiamin, riboflavin, and niacin [Afzaal et al., 2023]. Moreover, phenolics and saponins with antioxidant activities are reported in rambutan seeds [Chai et al., 2018]. Nowadays, rambutan seeds have been roasted and used as a snack food in the Philippines [Jahurul et al., 2020a]. Many studies have been performed to use rambutan seeds as a raw material to extract lipids [Sirisompong et al., 2011], proteins [Vuong et al., 2016] and various bioactive compounds [Sai-Ut et al., 2023].

In order to use rambutan seeds as a potential raw material to produce value-added products on an industrial scale, the seeds released from rambutan fruit processing industry processes need to be dried and preserved. Rambutan seeds contain lipase (LP) which catalyzes the hydrolysis of triglyceride to yield glycerol and fatty acids, thereby increasing the free fatty acid content during the drying process of rambutan seeds [Jahurul et al., 2020b]. Besides, fatty nuts and seeds contain lipoxygenase (LOX) [Shi et al., 2020], which catalyzes the oxidation of free fatty acids to produce peroxides and carbonyl compounds, resulting in rancid odors and harmful effects for human health [Liburdi et al., 2021]. In addition, polyphenol oxidase (PPO, EC.1.14.18.1) identified in many fruits [Villamil-Galindo et al., 2020] catalyzes the oxidation of phenolic compounds to form quinones, which can be polymerized to generate brown pigments such as melanin; these compounds negatively affect sensory attributes of the product [Dibanda et al., 2020]. Rambutan seeds are rich in lipids and phenolics [Jahurul et al., 2020a]. Inactivation of enzymes that promote phenolic and lipid transformation in rambutan seeds is essential before using the seeds in the making of value-added products.

Blanching is a conventional method to pretreat fruits and vegetables in the food industry, mainly to inactivate their enzymes and microorganisms [Chao et al., 2022]. Moreover, the blanching process can reduce the content of some anti-nutrients such as oxalate and phytate [Malhotra et al., 2023], prevent quality changes and shorten drying time for fruits and vegetables [Kim et al., 2020]. However, changes in enzyme activities and antioxidant contents in rambutan seeds during the blanching have not been considered.

In this research, rambutan seeds were blanched in hot water. The research objective was to investigate the effects of blanching temperature and time on the inactivation of LP, LOX and PPO as well as the loss in total phenolic and total saponin contents and antioxidant capacities of rambutan seeds. The antioxidant contents and capacities as well as the acidic and peroxide values of oil of the dried rambutan seeds during the accelerated storage were also evaluated to clarify the impacts of the blanching process on the quality of dried seeds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L., Java) fruits used in this study originated from a farm in Long khanh city, Dong nai province (Vietnam). About 100 kg of rambutan fruits were harvested after 115–120 days of flowering.

Chemicals and reagents

Linoleic acid was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) while vanillin, escin, catechol, gallic acid, Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radicals, 2,4,6-tri(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine, NaCl, KH2PO4, Na2CO3,and glycerol were bought from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All chemicals were of analytical grade. Gum arabic (code: GRM682-500G) originated from HiMedia (Maharashtra, India).

Blanching rambutan seeds

After separating the shell and flesh, the rambutan seeds were manually washed with tap water for 15 min. The blanching process was carried out in a thermostatic water bath (WNB14 model, Memmert, Schwabach, Germany). About 200 g of rambutan seeds were used in each batch; the ratio of rambutan seeds and water was 1/5 (w/v). The blanching temperature was fixed at 80, 85, 90 or 95°C, while the blanching time varied from 5 to 25 min. The blanched rambutan seeds were then cooled in 4°C water to ambient temperature for about 10 min and used for determination of LP, LOX and PPO activities as well as total phenolic and total saponin contents and antioxidant capacities. The unblanched rambutan seeds served as the control sample.

Accelerated storage of dried rambutan seeds

Rambutan seeds were blanched at 95°C for 25 min and cooled in water to about 70°C according to the blanching procedure reported above. The seeds were convectively dried at 70°C in a drier (SF30 model, Memmert) with hot air velocity of 2 m/s until the moisture content achieved 10-11%. The dried rambutan seeds put in polyethylene bags (about 200 g seeds per bag) were used for accelerated storage according to a reference of Lopez et al. [2022] with slight modifications. The dried seeds were preserved in an incubator (TH3-PE-100 model, Jeiotech, Daejeon, Korea) at 60°C, air humidity of 75% for 20 days. Every fourth day, samples were collected for determination of total phenolic and total saponin contents, antioxidant capacities, acidic and peroxide values. The control sample was unblanched rambutan seeds that were convectively dried under the same conditions.

Enzyme assays

To extract enzymes from rambutan seeds, about 10 g of seeds were added into 50 mL of a solvent; using 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) for LP, 1/15 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) for LOX, and 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) for PPO. The mixture was ground for 2 min using a laboratory mill (A11 model, IKA, Freiburg, Germany) and then incubated in a thermostat-shaker (Certomat BS1 model, B Braun Biotech International, Melsungen, Germany) at 30°C and 100 rpm for 30 min. The suspension was then centrifuged (Z366K centrifuge, Hermle, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) at 4°C and 10,000×g for 30 min, and the supernatant was used to determine LP, LOX and PPO activities.

The LP activity was measured following to the procedure of Mustranta et al. [1993] with slight modification. The substrate solution including 15 mL of olive oil and 35 mL of an emulsifying agent (1 L of an emulsifying agent contained 17.9 g of NaCl, 0.41 g of KH2PO4, 540 mL of glycerol, 10 g of gum arabic, and distilled water) was prepared by mixing and homogenizing (APV 2000 model, SPX Flow, Bydgoszcz, Poland) at ambient temperature; the pressure on the first and second stage was 350 and 80 bar, respectively. Then, 5 mL of the substrate solution was mixed with 4 mL of 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and 1 mL of the crude enzyme extract and the mixture was heated at 37°C for 10 min. Then, 10 mL of an acetone-ethanol mixture (1/1, v/v) was added to stop the reaction. The released fatty acids were titrated with 0.05 M NaOH solution. One LP unit is defined as an amount of enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of triglyceride to release 1 µmol of free fatty acids within 1 min under the assay conditions. The results were expressed as the number of units per g dm of the rambutan seeds.

The LOX activity was estimated according to the procedure posited by Gökmen et al. [2002] with slight modification. The substrate solution consisting of linoleic acid (157.2 µL), Tween-20 (157.2 µL) and deionized water (10 mL) was prepared by homogenization at 30°C and 200 rpm for 5 min. Then, 1 mL of 1 M NaOH solution was added to the obtained mixture, which was next diluted to 200 mL with 1/15 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), resulting in a 2.5 mM linoleic acid solution. About 29 mL of the substrate solution and 1 mL of the crude enzyme extract were added into a 100 mL Erlenmeyer flask which was put in a thermostat-shaker at 30°C and 100 rpm for 5 min. After that, 1 mL of the reaction mixture was transferred into a test tube, to which 4 mL of 0.1 M NaOH solution was added to stop the enzymatic reaction. The absorbance was then recorded at the wavelength of 234 nm. One LOX unit is defined as an amount of enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of linoleic acid to increase absorbance of the reaction mixture by 0.001 unit at the wavelength of 234 nm per min under the assay conditions. The results were presented as the number of units per g dm of the rambutan seeds.

The PPO activity was determined following a procedure presented by Zhang et al. [2018]. The reaction mixture was composed of 1.5 mL of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) and 1 mL of a 0.2 M catechol solution. About 0.5 mL of the crude enzyme extract was then added to the reaction mixture. The reaction was performed at 30°C for 2 min, and the absorbance was measured at the wavelength of 420 nm. One PPO unit is defined as an amount of enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of catechol to increase absorbance of the reaction mixture by 0.001 unit at the wavelength of 420 nm per min under the assay conditions. The results were shown as the number of units per g dm of the rambutan seeds.

Chemical analysis

About 30 g of rambutan seeds were ground in a laboratory mill (A11 model, IKA) for 2 min, and the milled seeds were defatted using a Soxhlet system. About 10 g of defatted rambutan seed powder was added into a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 100 mL of 80% (v/v) aqueous methanol; the Erlenmeyer flask was then put in a thermostat-shaker (Certomat® BS-1 model, B. Braun Biotech. International) at 30°C and 100 rpm for 30 min for extraction. At the end of the extraction, the suspension was centrifuged at 4°C and 10,000×g for 30 min and the supernatant was used to determine the total phenolic and total saponin contents and antioxidant capacities.

The total phenolic content was quantified by the spectrophotometric method according to a procedure reported by Le et al. [2024] with slight modification. About 0.2 mL of the diluted extract and 1 mL of the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent were added into a test tube. After that, 0.8 mL of a 10% Na2CO3 solution and 3 mL of distilled water were added, and the mixture was vortexed. The reaction occurred at ambient temperature in the dark within 30 min. The absorbance of the obtained sample was measured at the wavelength of 760 nm on a spectrophotometer (2600i model, Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan). The standard curve was established using a gallic acid solution with concentrations varying from 0 to 50 mg/mL. The total phenolic content was expressed as mg gallic acid equivalent per 100 g dm of the rambutan seeds (mg GAE/100 g dm).

The total saponin content was determined by the spectrophotometric method following a procedure described by Hiai et al. [1976] with slight modification. About 0.5 mL of the diluted extract and 0.5 mL of 8% (w/v) vanillin in ethanol were added into a test tube; after that, 5 mL of a 72% (v/v) H2SO4 solution were added into the tube, which was then put in cold water to adjust the mixture temperature to about 70°C. The mixture was incubated at 70°C for 20 min and then cooled to ambient temperature using cold water. The absorbance of the obtained sample was measured at the wavelength of 560 nm on a spectrophotometer (2600i model, Shimadzu Co.). The standard curve was established using an escin solution with concentrations varying from 0 to 1,000 mg/mL. The total saponin content was shown as mg escin equivalent per 100 g dm of the rambutan seeds (mg EE/100 g dm).

Antioxidant capacities were determined by DPPH and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assays, using procedures reported by Brand-Williams et al. [1995] and Benzie & Strain [1996], respectively, with slight modification. For the DPPH assay, 0.1 mL of the crude extract and 3.9 mL of the 0.1 mM methanolic DPPH radical solution were added into tubes, vortexed and incubated at ambient temperature in the dark for 30 min. The absorbance was recorded at the wavelength of 517 nm. For the FRAP assay, 0.6 mL of the diluted extract and 3.4 mL of the FRAP reagent solution were added into a test tube, vortexed and left at ambient temperature in the dark for 15 min. The absorbance was measured at the wavelength of 593 nm. Antioxidant capacity was presented as μmol Trolox equivalent per 100 g dm of the rambutan seeds (μmol Trolox/100 g dm).

Acidic and peroxide values were quantified by the AOAC International 940.28 and 965.33 methods, respectively [AOAC, 2000]. About 20 g of rambutan seed powder were added into 300 mL of hexane; the oil extraction was performed at about 65°C for 2 h in a Soxhlet system. The liquid phase was then subjected to vacuum evaporation at 45°C using a rotary evaporator (Model RV 3V-C, IKA) for hexane removal. The obtained seed oil was used for determination of acidic and peroxide values, which were expressed in mg KOH/g seed oil and meq/kg seed oil, respectively.

Determination of kinetic parameters of enzyme inactivation and antioxidant degradation during the blanching of fresh rambutan seeds and the accelerated storage of dried rambutan seeds

The kinetic parameters of enzyme inactivation and antioxidant degradation during the blanching of fresh rambutan seeds and the accelerated storage of dried rambutan seeds were determined using the first-order kinetics [Kayın et al., 2019], according to Equation (1):

where: Ct and C0 are the LP/LOX/PPO activity or the total phenolic/total saponin content at time t and zero; k is the first-order rate constant of enzyme inactivation or antioxidant degradation; t is the blanching time (min) or the accelerated storage time (day).Then, the logarithm of Equation (1) was used to get Equation (2):

In practice, the enzyme activity Ct and C0 expressed in U/g dry matter of the rambutan seeds can be replaced by the percentage of the initial enzyme activity.

From the experimental data, a graph showing the relationship between ln(enzyme activity or total phenolic/total saponin content) over time was established. The inactivation/degradation rate constant (k) and half-life (t1/2)were then determined; where k is the slope of the straight lines Equation (2) and t1/2 is calculated according to Equation (3):

The impact of temperature on the enzyme inactivation rate constant or the phenolic/saponin degradation rate constant follows a first-order Arrhenius plot between lnk and 1/T. The dependence of k on temperature (T) was determined according to the activation energy (Ea), according to Equation (4):

where: Ea is the energy activation of the reaction (kcal/mol); R is the gas constant (8.314×10-3 kJ/(K×mol); T is the absolute temperature (K); and C is the pre-exponential constant.The Ea value was calculated from the slope of the straight-line Equation (4).

Statistical analysis

Each blanching and accelerated storage experiment was done in triplicate. The results were shown as means and standard deviation (n=3) and subjected to analysis of variance, using Statgraphics Centurion XIX (Manugistics Inc, Rockville, MD, USA). Mean values were considered significantly different as the probability was less than 0.05 using least significance difference (LSD) multiple range test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Impacts of blanching temperature and time on lipase, lipoxygenase and polyphenol oxidase activities in rambutan seeds

Changes in LP, LOX and PPO activities during the blanching of rambutan seeds are presented in Figure 1. At the four investigated temperatures, the enzyme activities in rambutan seeds gradually decreased with the blanching time. After 25-min blanching at 80, 85, 90 and 95°C, the remaining LP activity was 76, 66, 59 and 46%, respectively (Figure 1A); meanwhile the remaining LOX activity was 63, 48, 39 and 32%, respectively (Figure 1B); and the remaining PPO activity was 44, 35, 32 and 20% compared to the initial level, respectively (Figure 1C). It can be noted that with the same blanching time, the PPO activity was reduced more than the LP and LOX activities. Therefore, LP and LOX needed longer heat treatment time than PPO to achieve the same inactivation level at the same blanching temperature.

Figure 1

Changes in lipase (A), lipoxygenase (B) and polyphenol oxidase (C) activities in rambutan seeds during blanching.

Our statistical analysis shows that the decrease in LP, LOX and PPO activities in rambutan seeds over the blanching time followed the Arrhenius first-order kinetic model of enzymatic reactions, as indicated by the coefficient of determination (R2) which ranged from 0.90 to 0.99 (data not shown). Previously, the changes in PPO activity in Agaricus bisporus mushroom [Cheng et al., 2013] and Aruncus dioicus var kamtschaticus samnamul [Kim et al., 2020] during the water blanching were also fitted to the first-order kinetic model.

The kinetic parameters of LP, LOX and PPO inactivation are visualized in Table 1. The higher the blanching temperature was, the greater was the inactivation rate constant of LP, LOX and PPO in rambutan seeds. Specifically, when increasing the blanching temperature from 80 to 95°C, the inactivation rate constants of LP, LOX and PPO increased 2.7 times, 2.3 times and 2.1 times, respectively. At 90°C, the PPO inactivation rate constant in rambutan seeds was 42.8×10-3 1/min; meanwhile that value in dragon fruit peel was 4.4×10-3 1/s [Mai et al., 2022], which is equivalent to 264×10-3 1/min, whereas that value in mangosteen peel was 17.1×10-3 1/min [Deylami et al., 2016]. Thus, the inactivation rate constant of PPO in rambutan seeds was much lower than that in dragon fruit peel but higher than that in mangosteen peel.

Table 1

Inactivation rate constant, half-life and activation energy of lipase, lipoxygenase and polyphenol oxidase inactivation in rambutan seeds at different blanching temperatures.

In contrast to the enzyme inactivation rate constant, the half-life of LP, LOX and PPO in rambutan seeds gradually decreased with the blanching temperature (Table 1). The higher the blanching temperature was, the shorter was the enzyme half-life. The half-life of LP in rambutan seeds was 1.43 to 1.68 times and 1.98 to 2.65 times higher than that of LOX and PPO, respectively. The thermal stability of LP in rambutan seeds was higher than that of LOX while the PPO showed the lowest thermal stability.

Among the three investigated enzymes in rambutan seeds, LP showed the highest activation energy of enzyme inactivation, followed by LOX and PPO (Table 1). It is reported that Ea of LP inactivation in wheat germ was 21.719 kJ/mol [Xu et al., 2016], which was 3.2 times lower than that of LP in rambutan seeds. Meanwhile, Ea of LOX inactivation in rambutan seeds was nearly similar to the value of LOX in lupine beans (60.5 kJ/mol) but much lower than that of soybean LOX (119 kJ/mol) [Stephany et al., 2016]. Besides, Ea of PPO inactivation in rambutan seeds was higher than that in dragon fruit peel (43.63 kJ/mol) [Mai et al., 2022], but much lower than that in pomegranate flesh (112.97 kJ/mol) [Rayan & Morsy, 2020] and in straw mushroom (214 kJ/mol) [Cheng et al., 2013]. Enzymes in various agricultural products have various activation energies of their inactivation due to difference in dimensional structure of protein molecules [Fante & Noreña, 2012]. In addition, the heat transfer rate inside agricultural products is dependent on their chemical composition, thereby affecting enzyme inactivation level [Gonçalves et al., 2010].

In this study, the inactivation rate constant, half-life and activation energy of enzyme inactivation for LP, LOX and PPO in rambutan seeds were calculated and reported for the first time, contributing fundamental information to rambutan seed biochemistry.

Impact of blanching temperature and time on antioxidant contents and capacities in rambutan seeds

Changes in the total phenolic and total saponin contents and antioxidant capacity of rambutan seeds during the blanching are shown in Figure 2. The total phenolic content in rambutan seeds gradually decreased during the blanching. The greater the blanching temperature was, the lower was the remaining total phenolic content in rambutan seeds. Specifically, when the blanching temperature was increased from 80 to 95°C, the decrease in the total phenolic content after 25 min was enhanced from 11.2 to 25.6%. That could be due to partial diffusion of soluble phenolics from the rambutan seeds into the blanching water. Moreover, high blanching temperature could cause some phenolics to be hydrolyzed or oxidized [Cao et al., 2021]. Previous studies also reported the loss of phenolic compounds during the blanching of carrot peels [Chantaro et al., 2008], spinach, swamp cabbage and kale [Ismail et al., 2004].

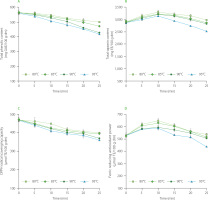

Figure 2

Changes in total phenolic (A) and total saponin (B) contents, DPPH radical scavenging capacity (C), and ferric reducing antioxidant power (D) of rambutan seeds during blanching. GAE, gallic acid equivalent; dm, dry matter; EE: escin equivalent; DPPH radical, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical; TE, Trolox equivalent.

The reduction in phenolic content in rambutan seeds during the blanching was fit to the first-order kinetic model with R2 varying from 0.90 to 0.99 (data not shown). Similar results were also recorded in the blanching of beetroot, eggplant, green pea, and green pepper within the temperature range of 70–90°C [Eyarkai Nambi et al., 2016].

Table 2 presents the kinetic parameters of phenolic degradation during the blanching. Blanching temperature increase from 80 to 95°C enhanced their degradation rate constant 2.3 times; on the contrary, their half-life time was significantly reduced. The degradation rate constant of phenolics in rambutan seeds at 90°C was 11.06×10-3 1/min, which was nearly similar to that in pitaya peel (2×10-4 1/s= 12×10-3 1/min) [Mai et al., 2022]. Thus, the thermal stability of phenolic compounds in rambutan seeds and dragon fruit peel during the blanching process was equivalent. Similarly, the activation energy of phenolic degradation in rambutan seeds (63.33 kJ/mol) and in dragon fruit peel (59.70 kJ/mol) did not differ significantly; however, these values were 1.95 times lower than that determined for carrot (123.51 kJ/mol) [Gonçalves et al., 2010].

Table 2

Degradation rate constant, half-life and activation energy of degradation of phenolics in rambutan seeds during the blanching at different temperatures.

| Temperature (°C) | Degradation rate constant (k) (×10-3 1/min) | Half-life (t1/2) (min) | Activation energy (Ea) (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80 | 5.13±0.32c | 135.4a | 63.33±4.12 |

| 85 | 7.03±0.40b | 98.7b | |

| 90 | 11.06±1.19a | 63.1c | |

| 95 | 11.73±1.28a | 59.5c |

Contrary to the changes in the total phenolic content, the total saponin content in rambutan seeds increased to the maximum during the early stages of blanching (Figure 2B). After 10-min blanching at 80, 85, 90 and 95°C, the total saponin content was 114, 111, 110 and 108% greater than that at the beginning of thermal treatment. A similar increase in the saponin level has recently been reported by Zhang et al. [2022] when Toona sinensis leaves were blanched at 100°C for 30 s, upon which the total saponin content increased by 62% as compared to the initial content in the leaves. It can be explained that the high blanching temperature could damage cellular membrane in the plant tissues, improving saponin extraction [Zhang et al., 2022]. Nevertheless, the saponin content in rambutan seeds decreased at the later stages of blanching. After 25 min blanching at 80, 85, 90 and 95°C, the remaining saponin content was 102, 99, 97 and 86% of the initial level, respectively. The reduction in saponin content was also reported in the noni (Morinda citrifolia L.) fruit [Kha et al., 2021]. The main reason is due to saponin degradation at high temperature [Liu et al., 2020]. Moreover, saponin loss could be a result of their release into the blanching water [Vuong et al., 2015].

Figure 2C shows that the DPPH radical scavenging capacity of rambutan seeds gradually decreased with blanching time. The higher the blanching temperature was, the lower was the DPPH radical scavenging capacity of rambutan seeds. At 25 min blanching time, the increase in temperature from 80 to 95°C augmented the loss in DPPH radical scavenging capacity in rambutan seeds from 15% to 23% compared to that at the beginning of blanching. However, the ferric reducing antioxidant power of rambutan seeds increased in the early stages of blanching and then gradually decreased. The antioxidant capacity measured by the FRAP assay after 25-min blanching was 102, 98, 95 and 83% of the initial value corresponding to the blanching temperature of 80, 85, 90 and 95°C, respectively. In this study, the changes in the total phenolic content and DPPH radical scavenging capacity of rambutan seeds were the same; meanwhile, the changes in the total saponin content and ferric reducing antioxidant power were nearly similar. Recently, Do et al. [2022] concluded that the total saponin content of Codonopsis javanica roots, especially the triterpenoid saponin content, were closely correlated with their ferric reducing antioxidant power. The quantitative changes in antioxidant contents and capacities in the present study provide important information to food technologists about the need to select appropriate blanching conditions in industrial production. Further study on phenolic and saponin profiles in rambutan seeds should be done to elucidate the correlation between the antioxidant contents and capacities of the seeds during the blanching treatment.

Impact of blanching on the quality of dried rambutan seeds during the accelerated storage

It can be noted that at the blanching temperature of 95°C and time of 25 min, the remaining activity of lipase, that was the most thermo-resistant enzyme in rambutan seeds, was less than 50% of the initial activity. These blanching conditions were selected to evaluate the impact of blanching conditions on the quality of dried rambutan seeds during the accelerated storage. Changes in the total phenolic and total saponin contents in the dried rambutan seeds during the accelerated storage are presented in Figure 3. The control sample was the unblanched rambutan seeds that were convectively dried under the same conditions.

Figure 3

Changes in total phenolic (A) and total saponin (B) contents, DPPH radical scavenging ability (C), and ferric reducing antioxidant power (D) of dried rambutan seeds, and acidic value (E) and peroxide value (F) of their oil during accelerated storage. DPPH radical, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical.

Generally, the total phenolic and total saponin contents in the unblanched and blanched seeds gradually decreased during the accelerated storage. At the 20th day, the total phenolic and the total saponin contents in the blanched seeds remained at 91 and 88%, respectively, as compared to those at the beginning of the storage, while those values in the unblanched seeds remained at 86 and 83% of the initial values.

Table 3 shows that the degradation constant rates of phenolics and saponins in the blanched seeds were 1.7 and 1.5 times lower, respectively, than those in the unblanched counterpart; on the contrary, the half-life of phenolics and saponins in the blanched seeds were much longer. These results confirmed that the blanching significantly reduced the loss in phenolics and saponins during the accelerated storage of the dried rambutan seeds. A recent study showed that after 16-week storage, the phenolic loss in the blanched-dried pitaya peel was 20.4%, while that in the unblanched-dried counterpart was 33.9% of the initial value [Mai et al., 2022].

Table 3

Degradation rate constant and half-life of phenolics and saponins during the accelerated storage of rambutan seeds.

Figures 3C and D show that the antioxidant capacities of the dried rambutan seeds gradually decreased during the accelerated storage. At the end of the storage, the DPPH radical scavenging capacity and ferric reducing antioxidant power of the blanched sample remained at 78 and 75% of the initial values, respectively, while the antioxidant capacities of the unblanched sample estimated by DPPH and FRAP assays were 72 and 64% of the initial values. These results were in agreement with the total phenolic and the total saponin contents in the dried seeds. The blanched-dried seeds had a lower loss in phenolics and saponins and greater antioxidant capacities than the unblanched-dried counterpart, confirming the significance of blanching in the treatment procedure of rambutan seeds.

Acidic value represents the degree of lipid hydrolysis during food preservation [Prescha et al., 2014]. During the first 16 days of the accelerated storage, the acidic value of rambutan seeds gradually increased to a maximum value and was 3.7 and 2.8 times higher than the initial value for unblanched and blanched seeds, respectively (Figure 3E). This observation confirmed that the triglyceride hydrolysis took place during the accelerated storage [Teimouri Okhchlar et al., 2024]. From the 16th to the 20th day of the storage, the acidic values in both samples gradually decreased due to enhanced oxidation of free fatty acids [Toci et al., 2013].

Peroxides are a representative compounds of primary oxidation products when lipids are oxidized [Xia & Budge, 2017]. The peroxide value of oil of the blanched-dried seeds remained unchanged during the first 12 days of the accelerated storage (Figure 3E); this value increased from the 12th to the 16th day and then decreased on the 20th day of the storage. However, the peroxide value of oil of the unblanched-dried seeds remained constant during the first 4 days; then it increased from the 4th to the 16th day, to ultimately decrease at the end of the storage. The maximum of the peroxide value in the blanched sample was 66% lower than that in the unblanched counterpart. Thus, the acidic and peroxide values in the blanched sample increased more slowly and less during the accelerated storage than those noted in the non-blanched samples. Similar results have recently been reported during the accelerated storage of the blanched and unblanched pomegranate seeds [Kaseke et al., 2021]. The reduction in the peroxide value at the later stages of the storage was due to the oxidation of peroxides into secondary oxidation products such as aldehydes, ketones, alcohols and short-chain organic acids [Choe & Min, 2006].

CONCLUSIONS

The blanching of rambutan seeds significantly diminished their LP, LOX and PPO activities. LP showed the highest thermal stability, followed by LOX and PPO. The total saponin content of rambutan seeds was enhanced during the early stages of blanching but decreased during the later stages, while the total phenolic content decreased successively during this thermal treatment. The reduction in the total phenolic and the total saponin contents and antioxidant capacities of the dried rambutan seeds was observed during the accelerated storage. However, the antioxidant loss of the blanched sample was lesser than that of the unblanched counterpart. Additionally, the increase in acidic and peroxide values of oil of the blanched-dried seeds was slower and lesser than those of the unblanched-dried seeds. Blanching treatment deactivated enzymes in rambutan seeds and effectively protected their antioxidants during the accelerated storage. Future study on phenolic and saponin profiles in rambutan seeds is essential to elucidate the correlation between their antioxidant contents and capacities during the blanching treatment.